‘Shadow Ticket’ review: Thomas Pynchon is at his finest

Book Review

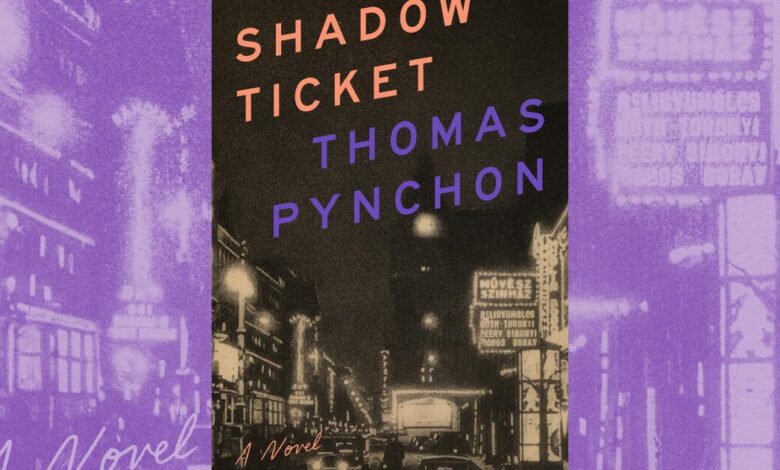

Shadow Ticket

By Thomas Pynchon

Penguin Press: 304 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

With next week’s publication of his ninth novel, “Shadow Ticket,” Thomas Pynchon’s secret 20th century is at last complete.

For many of us, Pynchon is the best American writer since F. Scott Fitzgerald. Since the arrival in 1963 of his first novel, “V.,” he has loomed as the presiding colossus of our literature — revered as a Nobel-caliber genius, reviled as impenetrable and reviewed with increasing condescension since his turn toward detective fiction with “Inherent Vice” in 2009.

Now comes “Shadow Ticket,” and it’s late Pynchon at his finest. Dark as a vampire’s pocket, light-fingered as a jewel thief, “Shadow Ticket” capers across the page with breezy, baggy-pants assurance — and then pauses on its way down the fire escape just long enough to crack your heart open.

Only now can we finally see that Pynchon has been quietly assembling — one novel at a time, in no particular order — an almost decade-by-decade chronicle no less ambitious than Balzac’s “La Comédie Humaine,” August Wilson’s Century Cycle or the 55 years of Garry Trudeau’s “Doonesbury.” This is his Pynchoniad, a zigzagging epic of America and the world through our bloodiest, most shameful hundred years. Perhaps suffering from what Pynchon called in “V.” our “great temporal homesickness for the decade we were born in,” he has now filled in the only remaining blank spot on his 20th century map: the 1930s.

A photograph of Thomas Pynchon in 1955. The elusive novelist has avoided nearly all media for more than 50 years.

(Bettmann Archive)

It all begins in Depression-era Milwaukee as a righteously funny gangster novel. In a scenario straight out of Dashiell Hammett’s early stories, a detective agency operative named Hicks McTaggart gets an assignment to chase down the runaway heiress to a major cheese fortune. Roughly midway through, Pynchon’s characters hightail it all the way to proto-fascist Budapest, where shadows more lethal than any Tommy gun begin to encroach. By the end, this novel has become at once a requiem, a farewell, an old soft-shoe number — and a warning.

When Pynchon’s jacket summary of this tale of two cities first surfaced six months ago, cynics could be forgiven for wondering whether an 88-year-old man, hearing time’s winged chariot idling at the curb, hadn’t just taken two half-completed works in progress and spot-welded them together. Younger people are forever wondering — in whispers, and never for general consumption — whether some person older than they might have, you know, lost a step.

Well, buzz off, kids. Thomas Pynchon’s voice on the page still sings, clarion strong. Unlike most novelists, his voice has two distinct but overlapping registers. The first is Olympian, polymathic, erudite, antically funny, often beautiful, at times gross, at others incredibly romantic, never afraid to challenge or even confound, and unmistakably worked at. The second, audible less frequently until 1990’s “Vineland,” sounds looser, freer, warmer, more improvisational, more curious about love and family, increasingly wistful, all but twilit with rue. He still brakes for bad puns and double-negative understatements, but he avoids the kind of under-metabolized research that sometimes alienated his early readers.

“Shadow Ticket’s” structure turns the current film adaptation of “Vineland” inside out — that would be “One Battle After Another,” whose thrilling middle more than redeems an only slightly off-key beginning and end. By contrast, “Shadow Ticket” offers a wildly seductive overture, a companionable but occasionally slack midsection, and a haunting sucker punch of an ending.

Mercifully, having already set “The Crying of Lot 49” and “Inherent Vice” largely in L.A., Pynchon still hasn’t lost his nostalgia for Los Angeles, a place where he lived and wrote for a while in the ’60s and ’70s. “Shadow Ticket” marks Pynchon’s third book to take place mostly on the other side of the world, but then — like so many New Yorkers — the novel finds its denouement in what Pynchon here calls “that old L.A. vacuum cleaner.”

Pynchon may not have lost a step in “Shadow Ticket,” but sometimes he seems to be conserving his energy. His signature long, comma-rich sentences reach their periods a little sooner now. His chapters end with a wink as often as a thunderclap. Sometimes he sounds almost rushed, peppering his narration with “so forths,” and making his readers play odds-or-evens to attribute long stretches of dialogue.

Maybe only on second reading do we realize that we’ve been reading a kind of Dear John letter to America. Nobody else writing today can begin a final chapter as elegiacally as Pynchon does here: “Somewhere out beyond the western edge of the Old World is said to stand a wonder of our time, a statue hundreds of meters high, of a masked woman. … Like somebody we knew once a long time ago.”

Is this the Statue of Liberty, turning her back at last on the huddled masses she once welcomed? One character immediately suggests yes, another denies it. Either way, it’s a sobering way to introduce an ending as compassionately doom-laden as any Pynchon has ever given us.

Bear in mind, this is the same Pynchon who, a hundred pages earlier, has raffishly referred to sex as “doing the horizontal Peabody.” (Don’t bother Googling. This one’s his.) One early reviewer has compared “Shadow Ticket’s” shaggy charm to cold pizza, and readers will know what he means. Who’s ever sorry to see a flat box in the fridge the next morning?

For most of the way, though, “Shadow Ticket” may remind you of an exceptionally tight tribute band, playing the oldies so lovingly that you might as well be listening to your old, long-since-unloaded vinyl. The catch is, for an encore — just when you could swear the band might actually be improving on the original — the musicians turn around and blow you away with a lost song that nobody’s ever heard before.

Thus, with a flourish, Pynchon types fin to his secret 20th century. But what does he do now? The man’s only 88. (Anybody who finds the phrase “only 88” amusing is welcome to laugh, but plenty of people thought Pynchon was hanging it up at 76 with “Bleeding Edge.” Plenty of people were mistaken.)

So, will Pynchon stand pat with his 20th century now secure, and take his winnings to the cashier’s window? Or will he, as anyone who roots for American literature might devoutly wish, hold out for blackjack?

Hit him.

Kipen is a former NEA Director of Literature, a full-time member UCLA’s writing faculty and founder of the Libros Schmibros Lending Library and the just-birthed 21st Century Federal Writers’ Project.

Source link