Reading the New Pynchon Novel in a Pynchonesque America

As for pace, “Shadow Ticket” reads like one of its subplots, about the Trans-Trianon 2000, a two-thousand-kilometre motorcycle circuit through the disputed territories of Central Europe, all speed and vroom. Uncharacteristically for Pynchon, the book never eddies off to explore some branch of science or mathematics or philosophy, and the moments when it slows down enough to let the reader actually look around are few and far between—a pity, because, when he wants to, Pynchon is wonderful at showing us the world. Here is a Nazi front disguised as a bowling alley, in the outer reaches of Milwaukee, the wintry Wisconsin night lit up for miles by the sign outside: “four or five different colors from deep violet to blood orange, bowling balls flickering left to right, pins scattering, reassembling, again and again, silently except for an electrical drone fading up slowly louder the closer you get to it.”

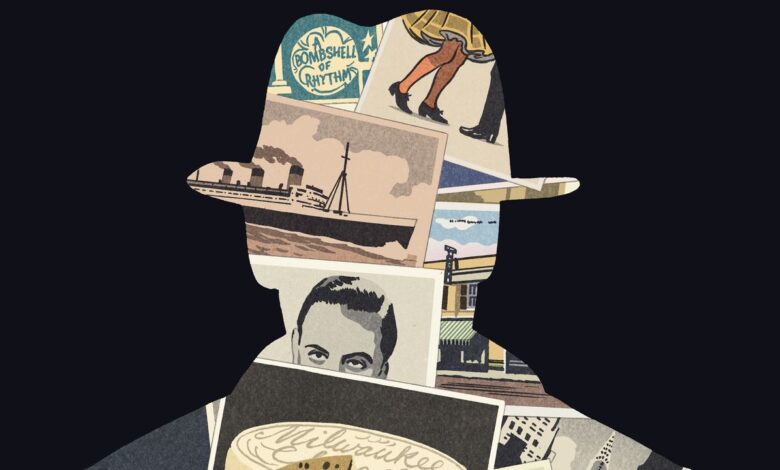

For the duration of that sentence, Pynchon is less Bosch than Edward Hopper, making us feel this scene by making us see it: the night and the neon, the gust of loneliness, the dangerous electric edge. On the whole, though, the author is not in the business of making anyone feel things. (The shining exception to this rule is “Mason & Dixon,” the only one of his novels that is not merely brilliant but also character-driven, thematically lucid, and profoundly moving.) His customary genre is farce—the rest of his characters are subordinate to the absurd situations they find themselves in—and his customary mode is that of the comic book, full color but two-dimensional. At one point, someone hands Hicks a live bomb on the streets of Milwaukee, which he barely manages to chuck into a fishing hole on iced-over Lake Michigan before it goes kaboom; later, a pair of spies escape a near-assassination in Transylvania by climbing the mooring lines of a departing zeppelin. In both cases, you can practically see the Benday dots and speech balloons. And the emotional register of the book stays mostly within the realm of the comic book, too: the good guys are good-guy-proofed against mortal danger; the bad guys are sinister but not frightening. Even the literal Nazis are never chilling, though they are sometimes chillin’. (Over beer and bratwurst: “We’re National Socialists, ain’t it? So—we’re socializing. Try it, you might have fun.”)

For a while, all this is perfectly enjoyable—Elmore Leonard meets Stan Lee, a kind of Technicolor noir. But, the further into “Shadow Ticket” you get, the more it starts to suffer, as many of Pynchon’s later novels do, from the presence of its predecessors. Consider the cheese underworld, a sphere of criminality so consummately Pynchonesque that it reads like self-parody. In who else’s fiction would you find price-fixing on the Wisconsin Cheese Exchange, bandits invading creameries up and down America’s Cheese Corridor, innumerable nefarious purveyors of counterfeit Emmental and Gruyère?

More important: What is all this doing in this work of fiction? From the beginning, Pynchon has put his readers in the position of his characters, encouraging us to see hidden significance and obscure connections within (and, later, among) his books, and as a result to grow steadily more paranoid with each passing page. Surely, we’re supposed to think, this cheese business must mean something—maybe even, as Pynchon teases, “something more geopolitical, some grand face-off between the cheese-based or colonialist powers, basically northwest Europe, and the vast teeming cheeselessness of Asia.” Or maybe Pynchon, who nearly killed off one of the title characters of “Mason & Dixon” with a giant wheel of Gloucester, is what you might call lactose intolerant. Or maybe he just thought it would be funny to write about the big cheese of Big Cheese.

Your appetite might differ, but for me, nine novels in, all this code-cracking and jigsaw-puzzling is no longer thrilling. The same goes for the other bells and whistles of Pynchon’s style; even a seventy-million-trick pony is still a trick pony, and much of what once seemed clever in his canon now seems tiresome. You will find, in “Shadow Ticket,” countless texts within the text, including the usual LP’s worth of songs—“Midnight in Milwaukee,” “Bye-Bye to Budapest.” (“Boo, hoo, hooo-dapest,” the singer croons.) You will find golems. You will find ghosts. You will find, if you bother to investigate, real-life oddities poached from the past because they come across like pure Pynchon invention—among them Clara Rockmore, a famous theremin player (Pynchon presumably appreciates her name), and a shoe-store X-ray machine for superior fittings, which not only really existed but really was produced by a Milwaukee company. You will find the aforementioned weird forms of transportation: that appropriated U-boat, an autogiro, an enormous motorcycle built to accommodate three German sleight-of-hand artists—Schnucki, Dieter, and Heinz, who collectively sound like a Minnesota personal-injury firm. And you will find, inevitably, characters with stranger names: Dr. Swampscott Vobe, Assistant Special Agent in Charge T. P. O’Grizbee, the noted illusionist or possibly genuine article Zoltán von Kiss. (As for our nomenclaturally modest hero, Hicks McTaggart, he is presumably named for J. M. E. McTaggart, an influential British philosopher who espoused the quasi-Pynchonesque beliefs that time is an illusion and that the human soul, connected to others of its kind by love, is the fundamental unit of reality.)

This one-man-band blare never quiets, but the music darkens considerably toward the end of “Shadow Ticket.” Jew hatred spreads and intensifies, Europe becomes a place to flee, and unrest over the price of milk in the United States results in a coup in which F.D.R. is toppled and General Douglas MacArthur seizes power. Stuck in exile, Hicks takes up with a motorcycle-riding Hungarian hottie but longs for Milwaukee, where the air smells like grilled bratwurst and sounds like accordion lessons and life “seldom gets more serious than somebody stole somebody’s fish.”

By then, I longed for Milwaukee, too—for the antic early pages of “Shadow Ticket,” when something coherent seemed to be forming beneath the fun. Instead, we get a darkness that is not just moral but epistemological. A suicide in a Budapest bathroom, a secret community of people sexually attracted to tasteless lamps, a movie plot entirely about violence and overeating: this stuff isn’t Bosch; it’s bosh—absurdity for absurdity’s sake, with no discernible aesthetic or intellectual purpose.

Source link