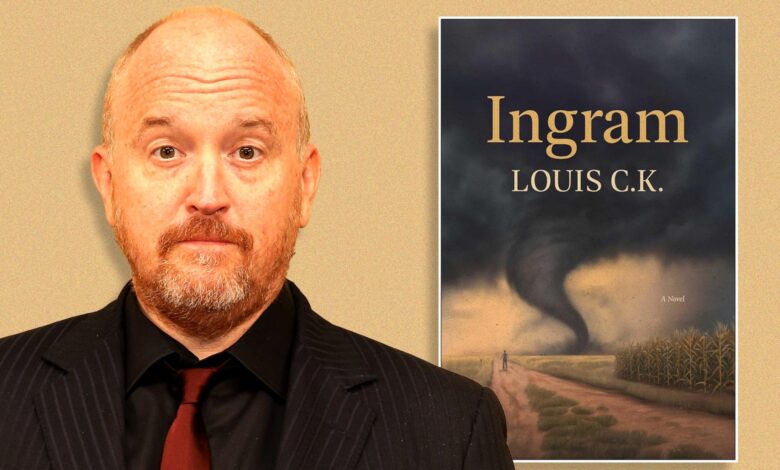

Louis C.K. book review: Ingram is a mess.

Six months ago, Louis C.K.—the once acclaimed comedian disgraced by revelations of sexual misconduct in 2017—announced in an email, “Turns out I’m also a novelist.” Ingram, C.K.’s newly published first novel, is, as he warned his mailing list, “not a comedy book. It’s a literary novel. It is literally a literary novel.”

It’s also a bit of a mess. Narrated by the title character—described by C.K. as a “simple but eloquent country boy”—Ingram relates the wanderings of a 9-year-old with zero experience of the world through a hardscrabble East Texas landscape. At the beginning of the book, Ingram explains that he spent his early childhood on an isolated farm, sitting in the dirt, watching his family’s pigs, dogs, chickens, and other animals. At some point, his father takes him into town “to see about me going to school,” marking the first time Ingram—who for some reason is brought to this meeting barefoot—has ever left the family property. School never happens because “they don’t have a bus that come here.” The farm is repossessed; Ingram’s abusive, alcoholic father vanishes; and his mother sends him out onto the road alone, telling the child, “There’s no home or family here now. Your luck and lot are worse here than anywhere else in the world.” All this by Page 7.

The reader will puzzle: When is this novel set? The family’s plight and isolation suggest the Great Depression, yet the descriptions of traffic—many cars and large trucks—indicate a more contemporary setting. If Ingram is set during, say, the second half of the 20th century, then why don’t child-welfare authorities intervene on Ingram’s behalf, insisting that he go to school, be adequately fed, and be allowed to sleep in the house instead of a shed? Early in his travels, Ingram meets a homeless man, the first Black person he has ever seen, who informs him that their society is strictly segregated by race. Is it the 1950s? But no, a massive aircraft shadows Ingram as he trudges down the road. Much, much later, a character references wanting to visit the moon, and it finally emerges that Ingram is set in some dystopian future.

By Louis C.K. BenBella Books.

Slate receives a commission when you purchase items using the links on this page.

Thank you for your support.

Ingram, of course, doesn’t understand where he’s situated in history. He can’t read or write, and his parents are largely silent. He doesn’t know what the words seems and story mean until characters he meets on the road explain them. This extreme deprivation, along with his parents’ abandonment, seems like enough trauma to incapacitate or destroy a child, but instead Ingram is openhearted, sincere, and curious, a cross between Candide and Huckleberry Finn.

It’s easy to see what C.K. is aiming for here: He wants to depict a harsh world as seen through the eyes of a guileless child, a blank slate who will simply report what he says without judgment. To do that, C.K. has to separate Ingram from his parents as quickly as possible. Most novelists do this by killing the parents off; Dickens made a habit of that. But C.K. needs the novel to end with a reconciliation of sorts with the past, so he must keep Ingram’s parents alive yet absent. In truth, C.K. really isn’t interested in Ingram’s childhood and how it might have shaped the boy, what would naturally be the concerns of a “literally literary” novelist. That’s because Ingram is driven by concept rather than character, and C.K. aspires only to concoct a narrator as naive and transparent as possible without worrying too much about how he got that way.

Most of what doesn’t make sense in Ingram is the obvious result of such calculations and can be readily reverse-engineered. Families as isolated as Ingram’s almost always have religious or conspiratorial reasons for cutting themselves off from the outside world. But if that were the case with Ingram’s parents, they would have surely filled him with ideas and theories that would spoil his innocence. What mother sends her 9-year-old child off to wander the world instead of struggling to keep him or at least trying to find someone else who could care for him? Only a woman suffering from severe mental illness or addiction issues, but these factors and their effect on Ingram would only interfere with C.K.’s scheme.

There are work-arounds for this problem. A writer can get away with a certain amount of psychological implausibility by adjusting the tone of the novel. With a third-person narrator and language stripped down to essentials, Ingram might have taken on the archetypal aspect of a fairy tale, in which characters’ motivations and inner lives are externalized or simply unexplained. But C.K. has instead adopted the tone and style of realist fiction, which leads readers to expect a novel’s fictional world to abide by the rules of the one we live in. As a result, readers of Ingram spend all their time wondering What was Ingram’s mother thinking? and Where is child protective services? rather than paying attention to what C.K. really cares about, which is describing what a freeway overpass might look like to someone who’s never seen one before.

It doesn’t help that C.K.’s rendering of rural poverty feels inauthentic. Children on struggling farms don’t spend their days sitting in the dirt, staring at animals. They work. What farm child would say “I knew what dead meant, too, though I couldn’t remember from what” or be utterly ignorant of sex, when both facts of life are a regular spectacle for anyone raising livestock? Ingram emits folksy utterances, like “Crying won’t fix anything. But it has a way of putting you back where you were before the trouble began,” that read like homilies from a Hallmark movie.

Ingram seems most of all like the kind of first novel that ends up in a drawer and stays there.

The most intriguing aspect of Ingram are the glimpses of the larger society its hero inhabits. Ingram and a temporary companion arrive in Austin—in our current reality, the site of a flourishing politically incorrect comedy scene—to find an incomprehensible cityscape of silent cars, manicured lawns, and residents dressed in “clean and pretty, bright colorful clothes,” including some men “who had on skirts and even dresses and some ladies had beards. Everyone was walking and talking even if they didn’t have a person next to them to talk to.” This, it turns out, is “New Austin” and, as a police officer tells Ingram before ejecting him, not “a place for someone like you.” Presumably, New Austin is populated by the kinds of people who are moving off-planet, a privileged class who eat the corn Ingram will be hired to harvest and burn the oil he will risk his life helping extract from the earth. But since Ingram really doesn’t understand such matters, the reader learns very little about them.

To be fair, C.K. set himself a formidable task. An experienced (and perhaps more gifted) novelist might have found a way to convey more—and more meaningful—information about Ingram’s world via the narrator’s highly limited viewpoint, as Mark Twain did with Huck Finn. A writer with a particularly fierce vision and style can command a reader’s belief in a fictional world despite some ramshackle world-building, as Cormac McCarthy did in The Road, a work that seems to have influenced Ingram. But C.K. is not that novelist.

Which is not to say he couldn’t be. Ingram seems most of all like the kind of first novel that ends up in a drawer and stays there until its author dies, whereupon, if the writer’s fully realized works have won over enough readers, it might get dragged out and published by the artist’s heirs. But C.K. is famous and still has many fans despite his scandals, and what ought to have been cashiered as mere juvenilia winds up printed between hardcovers, with a slipcover photo of its author sitting at a manual typewriter, and listed for $27.95. This choice does no one any favors, most especially C.K., who might have a genuinely worthwhile novel in him if he had the incentive to work harder and longer at the craft. Instead, he’s just sitting in the dirt.