Indies Introduce Q&A with Helena Haywoode Henry

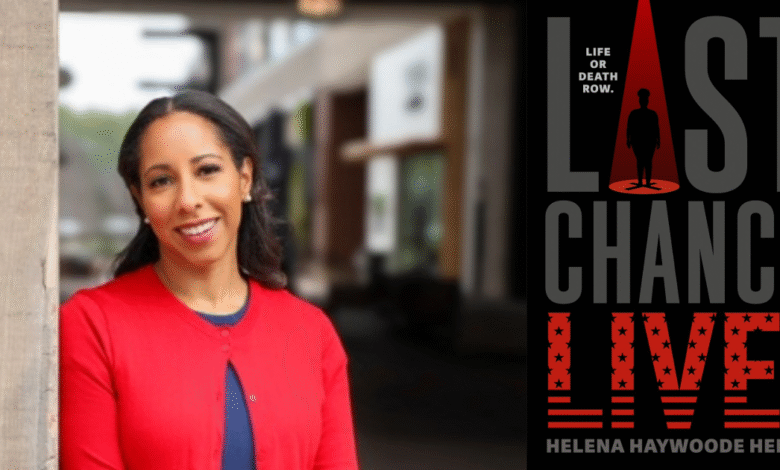

Helena Haywoode Henry is the author of Last Chance Live!, a Summer/Fall 2025 Indies Introduce selection.

Grace Lane of Linden Tree Books in Los Altos, California, served on the panel that selected Haywoode Henry’s book for Indies Introduce.

“I felt sick the whole time I was reading this book,” said Linden. “Helena sees so clearly a reality we’re swiftly moving to — one we’ve been swiftly moving to, echoed in books like Fahrenheit 451 and The Hunger Games and movies like Death Race — and she deftly managed to make us care about everyone and worry about the end. Try to read more slowly, to delay getting there. This one is going to stay with me for a long, long time and I can’t wait to recommend it to everyone I know.”

Haywoode Henry sat down with Lane to discuss her debut title. This is a transcript of their discussion. You can listen to the interview on the ABA podcast, BookED.

Grace Lane: Hello, I’m Grace from Linden Tree Books in Silicon Valley, California, and I am here to chat with debut author Helena Haywoode Henry about her book Last Chance Live!, which was an Indies Introduce pick for Summer/Fall 2025. Helena is a mom of three and a former attorney living in the Raleigh-Durham area. She graduated from the University of Pennsylvania and from NYU School of Law.

Welcome Helena!

Helena Haywoode Henry: Thank you, Grace. I’m so happy to be here!

GL: I’m so happy to be here with you. We have a lot to cover, because your book is intense in all of the best, worst ways. Every time I tried writing an interview question, I started writing an essay.

HHH: That’s the point of the book!

GL: Yes, exactly! The tagline for the book compares this to Squid Game, which is not an incorrect comparison, but to me, it’s similar to The Hunger Games.

You put a bunch of kids into a situation and they win or they die, all for public consumption, only the deaths in Last Chance Live! are sanitized, of course, [they’re] off screen where the voting viewers don’t have to watch a kid die scared and alone. I could see something like this being, in a few hundred years, the inspiration for those in The Capitol in The Hunger Games. What do you think of these comparisons?

HHH: I’m flattered by the comparison to The Hunger Games. I deeply admire Suzanne Collins’ work. There are broad parallels between The Hunger Games and Last Chance Live!, in that they both feature a contest in which there’s one winner and everyone else faces death.

They come from the same ancient story that shows that there’s an eternal hunger — no pun intended — for these types of tales — the story of Theseus and the Minotaur from ancient Greece. But in many ways, The Hunger Games and Last Chance Live! are quite different; I’m writing about this ancient type of tale in a real-world context.

To my mind, it’s impossible to separate how this would operate in the real world, disentangled from the realities of how race works systemically in America and how it has worked historically through the globe. The function of race in who is a tribute or who is at The Capitol is not a uniquely American phenomenon. It’s something that we’ve seen in broad strokes in every society through all of history. Who is an oppressor and who is the oppressed, largely, historically, falls around along racial lines. The reason for that is explored by a lot of great anthropologists who do excellent scholarship in this area, but it’s not anything innately inferior about people of color. To simplify a complex idea, it’s about ecological packages that different parts of the world have gotten, and how those created advantages over time.

All that is to say that Last Chance Live! is capturing a long-term truth of humanity in putting that real world, racial context into the book, not because it’s advocating for a political perspective, but because it’s a reflection of humanity and how we work.

GL: I would love to take college classes from you.

Our criminal justice system is not good. Guilty people go free — especially if they’re rich and white — and innocent people are just thrown in jail. It’s very expensive to keep someone in prison and that’s the monetary win for the winner of this — the money that it would cost to keep them in prison. We see for-profit prisons popping up all over the country. The recidivism rate is really high. We’re even seeing for profit orphanages.

Now that you have researched this book a lot, what would you like to see changed in our system, especially for young offenders? Because that’s who you’re really focused on in Last Chance Live!. How can we change the system and the carceral state to help the society that we have outside the prison walls, but also the people who are inside, who are predominantly Black, with not as much education and opportunities as other people have gotten?

That’s the thing that hurts me when I think about it, I’m like, “Why? Why are so many of these people in prison? It’s because society didn’t want to do anything else with them.”

HHH: We can’t change these systems without changing the ethics of the society that creates them. So the answer is actually a big one, but it’s also a hopeful one, because it gives every individual reader the opportunity and agency to be a part of that transformation. You don’t need to wait on policies. You don’t need to wait on one party or the other to affect change.

We are a deeply individualistic society. The forces that you’re talking about like, there’s capitalist dynamics at play and whatnot, but at the root of everything is that America is very much a “me first” country. It’s that cowboy ethic, you know, my frontier, my rights, my land, my my my.

One thing that I hope Last Chance Live! does is position Eternity Price, the protagonist, as a stand in for all of us — someone who is actually experiencing the same challenges of the human condition that we all are. I hope that encourages us to think of other people, not as a zero-sum game or a war for who gets to have their rights and who doesn’t, but instead challenges us to think in a collectivist kind of way. Instead of “me first,” what if I said “you first?” What would that look like, and how would these systems change?

The answer to that is something I’m actually exploring in my next book. I can’t talk about that much, but it’s a question that some public intellectuals have posed, which is, does America need a third founding, and what would the animating principle of that be?

If that first founding was 1787, animated by all men are created equal, and the second founding was 1865 animated by the 13th through 15th amendments, America seems to be teetering on the precipice of needing something new. This individualism is breaking down the nation. What animating principle could help save people like Eternity and people like us? Would a “you first” mindset be a solution there?

GL: Hearing you talk makes me feel hopeful.

HHH: That’s my hope! That’s really what I hope for readers to take away from Last Chance Live!, because, ultimately, the book is not a traditional story where you meet a hero and passively cheer them on.

The book is a case study, it’s a framework that positions the reader, in many ways, as the main character — both because Eternity is a mirror for our own human condition, but also because the brightest reflection of hope and change and repair is the reader. It’s what the reader chooses to do with the questions that Last Chance Live! raises and invites the reader to answer. I sometimes think the real story of the book is beginning after the last page, because the full story of Last Chance Live! is what happens in the real world.

GL: That’s such a beautiful way to put it. One of the themes in your author’s note is mercy. Who gets it? Why? Where does it come from? And how can we live in a society where we don’t necessarily have mercy for others, especially for children?

If anyone is thinking about listening to this book, I really highly recommend it. Helena reads the author’s note herself.

HHH: Yeah, and the actress for Eternity is incredible. She is just incredible.

GL: The actress for Eternity is so good. I was rereading my bound manuscript that I got earlier this year, and I actually didn’t have the author’s note in that, so I was really glad when I saw that it was on audio already and I could listen to it. I think I got a lot more out of it from your voice saying the words too.

HHH: Thank you. We first need to understand what’s happening that makes a society unjust or characterized by a lack of mercy. When some of us are living in an unmerciful society, that actually means all of us are, because we’re not two societies, we’re just one in this country.

GL: We’re not free till everyone’s free.

HHH: Right! Last Chance Live! is depicting a world that’s already happening. It might not be happening on a reality TV show, but it’s already happening. We already live in a culture of public executions. The hatred that infects our systems, that infects our prisons, it seeps out into the public square and it affects all of us. We go about our day — not to be too morbid — but running the risk that, just like Eternity Price, we will not get a last meal. We go to our schools and restaurants and movie theaters knowing that that is a uniquely American phenomenon, and it comes from somewhere.

The question is, why? What type of hate and evil has really taken root that has led American culture to be the one that Last Chance Live! shows? Why is there not much of a gap between Last Chance Live! and reality when there should be? And what’s the answer to that? Mercy is the answer to that.

Which begs the question, what is mercy? Mercy is ultimately forgiveness. Mercy is a paid bill. For the individual reader, as they contemplate the role of mercy in Last Chance Live!, I would invite them to think about how they can practice mercy individually.

The executive producer of Last Chance Live! talks about why forgiveness is a paid bill, and he uses a car crash analogy. If I crash my car into yours, and I cause $10,000 worth of damage, Grace, you can say, “Helena, I forgive you, but you still got to pay that bill. It’s not just going to go away.”

The concept of paying bills, of us individually in the real world, swallowing the harm that other people have done and paying their bills, so that American society can be a merciful one, is hard, but it’s something that every individual reader can do on their own. It’s easier to do when we think about the fact that we have paid bills or bills that need to be paid ourselves. I can contemplate the people who do me harm in my country, those who dehumanize and devalue people of color, people of marginalized statuses, those who seek to exclude me from public conversations or spaces. I may have access to unique privileges that give me an entryway into that nonetheless.

But do people like me, like Eternity, have that same privilege? How do I respond to that type of hatred? How do I pay that bill? I do it by contemplating my own bill.

This is where I think the Civil Rights Movement was essential and one of the greatest gifts that this country could have ever received. The Civil Rights Movement was grounded in a robust doctrine and philosophy of mercy. That’s really what it was about. It was showing us this model of what forgiveness looks like. How do you forgive white supremacy? How do you pay a bill yourself and swallow the harm and the pain? That model showed us what it looks like to overcome.

We’re not there yet, but we can get a sense that this is not the end. We are co-authors in this story of mercy and justice in this country. We see the role that mercy and forgiveness plays, and we see a model in the Civil Rights Movement of how we can participate in creating the story of America to look different than what it does today.

GL: I get weepy when I hear you talk about that; it’s such a beautiful dream. I want to hold on to those feelings of hope, because I don’t have them very much.

One smaller plot line that I really appreciated is Black hair and how Hollywood makeup and hair artists don’t know what to do with Black hair or Black skin tones (or any non-white skin tones). This is not just due to the racist reality of reality TV. Many A-list Black actresses have talked a lot about doing their own hair before getting to set, providing their own wigs, redoing what the “professionals” get wrong, and things like that. This is, of course, just another way racism is ingrained within America.

Are there any more of these background story lines that I didn’t catch as a white woman, that you feel comfortable talking about?

HHH: There’s actually a bigger point that the running hair storyline is making, and it’s one that’s ultimately about pluralism. We have this ideal of being a pluralistic country, but we can’t really be pluralistic in the public square if we’re not pluralistic in our culture. When you examine what is the default in a culture, what messages does culture send about who is normal? What is normal hair on your shampoo bottle, and what is abnormal, which is the implication.

That is a harm to everybody; it’s not just a harm to people who are excluded by it. There is so much beauty in the literal rainbow of experiences and shapes and sizes and colors and everything that humanity offers; it’s what makes America unique and great and very distinct from other nations. We are not like some other nations, a homogenous group of people that share a single ethnicity or religious tradition or cultural tradition. The only thing that groups us together is our pluralism.

So if, in our cultural spaces, in fashion, in media, and hair and makeup, we can’t figure out how to honor and respect that pluralistic aspect of America, we’re certainly not going to have it in any bigger spaces that are more consequential than hair. The book is inviting readers to contemplate how they can be an advocate for pluralism, which is going to include people who are different from me. There’s that mercy analysis, regarding people who don’t believe what I believe. That’s the only thing that’s American, essentially. That’s the only thing that binds me to them, that we are different, and therefore we are American. So the hair is just that concept, but writ small.

GL: I love that. That’s so beautiful. You have called this book speculative fiction. It very barely is speculative fiction, because this could be happening right now. We’re not quite at the reality show of death yet, but we’re not far off from it. As you point out early in the book, America kills its children, whether we want to or not, through poverty and food deserts and generational emotional trauma of racism, and hatred of women and girls, and school shooting after school shooting, and we see all of it through the internet and the 24-hour news cycle.

Now that you’ve talked about this book a lot over the course of this year, and you’ve done all the research, and you’ve done all the talking, is there anything to hope for Helena?

HHH: Absolutely! I think a lot about why stories resonate with us — not just Last Chance Live!, but all stories — and why these stories broadly share the same universal structure, and it’s because there’s something external about stories. Stories don’t just exist within text. There’s something real about the force and the framework of how a story works. I think that we sense that we’re living in a story. Not in a fictitious way, but that we are all participating in a co-authorship of a story of a country, a nation, a world.

The hope is in two things. One, this is not the end. This might be the dark night of the soul. This might be the midpoint, maybe we’re at the inciting incident, I don’t know where we are, but this is not the end. The second facet of that hope is we have the agency to be co-authors. We have the agency to help write what it is we want the arc of the story to look like. That’s why I say the main character of Last Chance Live! is the reader. That’s why I say the brightest reflection of hope is in the reader. That’s why I say the story of Last Chance Live! begins after the last page, because there is so much that we have the ability and agency to do if we choose to.

GL: That is such a beautiful way to end it. I’m getting weepy listening and finding hope that I feel like I’ve lost this year. Thank you very much for writing this book. I really look forward to your next book.

HHH: Thank you for having me.

GL: Thank you for finding the threads of hope, and not inevitability. That’s really amazing.

HHH: Thanks so much, Grace. This has been a fantastic talk.

GL: Thank you for listening, everyone!

HHH: Take care.

Last Chance Live! by Helena Haywoode Henry (Nancy Paulsen Books, 9780593625309, Hardcover, YA Fiction, $21.99, On Sale: 10/7/2025)

You can learn more about this author at helenahenry.com.

ABA member stores are invited to use this interview or any others in our series of Q&As with Indies Introduce debut authors in newsletters and social media and in online and in-store promotions. Please let us know if you do.

Source link