Indies Introduce Q&A with David Greig

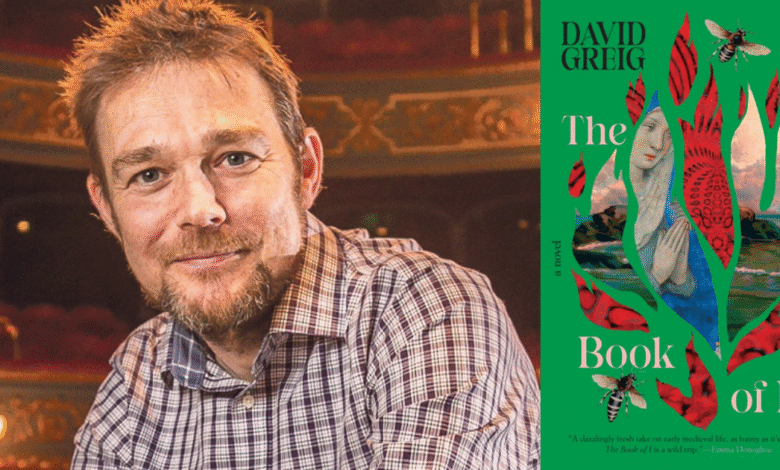

David Greig is the author of The Book of I, a Summer/Fall 2025 Indies Introduce adult selection.

James Crossley of Leviathan Books in St. Louis, Missouri, served on the panel that selected Greig’s book for Indies Introduce.

“A fictional account of a Norse raid on a Scottish island monastery that is respectful of the vast gap in time between its setting and the present day, but also irreverently funny as it demonstrates how little human character has actually changed in the last thousand years. The Book of I is an assured, accomplished debut,” said Crossley.

Greig sat down with Crossley to discuss his debut title. This is a transcript of their discussion. You can listen to the interview on the ABA podcast, BookED.

James Crossley: Hi, I’m James Crossley. I’m the owner of Leviathan Bookstore in St Louis, Missouri, and I was a bookseller member of the panel that selected the books chosen for the Indies Introduce program this fall. I’m here with one of those authors.

David Greig is a Scottish writer whose plays have been performed widely in the UK and around the world. His theater work includes The Strange Undoing of Prudencia Hart, Touching the Void, Midsummer, The Events, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Local Hero, and Dunsinane. From 2015 to 2025 he was the Artistic Director at Edinburgh’s Lyceum Theatre. The Book of I is his first novel.

That book was one of the first that I read when we were going through the submissions and — no slight to the many other wonderful books that we chose — this was also one of the first that I knew was going to be on the list.

David, welcome!

David Greig: Thank you very much. It’s really lovely to be here. It’s a thrill. I’m speaking from Scotland. When one writes a novel, particularly one’s first — quite late in life, in a way, compared to other people — I didn’t really expect it to go anywhere. I know that with most novels, you’re really lucky if you sell a few hundred in your local community. To know that it’s reached America is just so joyful. Thank you for having me, and thank you for this chance to talk about it.

JC: It’s my pleasure. Your story is set on the Isle of Iona in the ninth century, which is sometimes known by its initial letter. Can you tell us about what that place was like, and how the book grew out of that landscape?

DG: Iona is an island off an island. It’s a small, very beautiful island off the bigger island of Mull, which is off the west coast of Scotland. In the ninth century, that was part of a kind of pan-Irish-Scottish kingdom called Dál Riata.

It was an early Christian kingdom. In fact, one of the things that people don’t really know is that when Christianity came to Britain, it came from Ireland and the west coast of Scotland, which was where the church fathers who founded Christianity in Britain — sometimes called the Celtic Church — were from.

One of the most important of those figures was a man called Saint Columba. He was already a very famous religious writer and figure. Monks and monasteries were a really big part of this culture, and they were incredible recorders of history and makers of books and peace treaties. They were really important figures, and in some ways, they were the most sophisticated thing that Britain or these islands had seen since the Romans had departed. Columba, later in his life, founded an abbey on Iona and that abbey became the capital of Christian culture in the West of Scotland.

So about three hundred years had gone by since he founded it, and the issue is that the Vikings had started to raid the British coast, particularly the monasteries. They loved monasteries, because monasteries had all kinds of things that you could attack, and monks in general didn’t fight back. They’d already raided Iona a couple of times, to the extent that the kings of Dál Riata suggested that the monastery be moved to the middle of Ireland, away from where the Vikings go. This is all true, by the way.

One abbot really wanted to be a martyr — it’s a different sort of Christianity than we’re used to — he wanted to die for God. He said, “No, no, no, we will rebuild and keep Iona going.” For 25 years, he ran the community of monks on this island, but knows that any day death could come in the form of a raid.

During this period, they make books. One of the books they make ultimately becomes what we know as the Book of Kells. It’s a really famous medieval manuscript; it’s the first four gospels and it’s beautifully illustrated. Kells is a monastery in the middle of Ireland, but actually, what has been discovered recently is, in all likelihood, the bulk of the book was made on Iona. During this period, when the monks are both waiting for this terrible death that they know is almost certainly coming, they are also making this beautiful illustrated Bible.

One day in 825, there was a Viking raid, and all the monks were killed. That is the true story.

I’ve imagined what would happen if one of the Vikings was accidentally left behind by his gang and if also, by a miracle, one of the monks survived. There are another couple of people who then turn up in the book as well, but it becomes a story of how these people find a way to survive, get along, and pass the summer on the island whilst they wait for the autumn raiding season, when the they know the Vikings will come back to finish the job.

JC: It’s almost like the very contemporary futuristic novel The Martian, where one man is left behind.

DG: Yeah! Actually, I hope I don’t give too much away, but I was quite inspired by Witness, with Harrison Ford amongst the Amish. I was really interested in this idea of a gangster amongst peacemakers, which is really what Witness is. I find that really fascinating.

I became interested in Celtic Christianity because it was very revolutionary at the time in ways that we slightly forget. This was a world of utter warlordism, a very, very violent world and it was pagan.

All of that was predicated on the idea that it was good to be strong and kill people. If gods were with you, that’s what would happen. If gods weren’t with you, you’d be weak. The idea of a religion that was founded on the idea that you might want to be weak, or you might want to be humble, was completely insane to these people. I mean, they looked at it and just went, “You’re mad! What are you talking about?”

I thought that would be quite an interesting, funny place to begin, to sort of have this encounter. Also, the availability of a love story, because the third character is the woman who makes the mead — the honey beer that fed the monks. She’s very good at it. She survives the raid as well. It becomes a story of the Viking, the monk, and her together.

JC: It’s very interesting that that weakness that you talked about: the abbot, the monk in charge of the whole thing, is basically offering himself as a sacrifice, but in so doing, is also squandering the lives of all the people who are under him who wouldn’t necessarily have made that choice.

DG: In a way, I wanted to make Christianity strange, in order to possibly then make it interesting again. In America, obviously you have a different relationship with religion. I think it’s much more present in daily life than it is in Britain. We’re a much more secular country.

I wanted to make Christianity seem very odd. One of those assumptions we make, for example, is that it’s not a good thing, generally, to be massacred. Yet I wanted to remind people that there was this moment where some people certainly felt that to be sacrificed in the name of God was one of the best possible things that could happen to you.

JC: That is a very weighty subject, but the book does not read that way. You’re dealing with war, you’re dealing with religion, you’re dealing with all these issues, but it’s a very funny book. In my opinion, there are not nearly enough comic novels in general, and few of those comic novels make it onto awards list. Did you set out to make the book funny, or is that just how the story came out as you wrote it?

DG: A little bit of both. In my theater work, I always have a lot of humor. Very few of my plays don’t have any jokes, and I think it’s just the way I write. If I think things are funny, I just think they’re funny, and there’s not much I can do about it. When I tackle a subject, I will start to uncover things that make me laugh, and I want to explore in that way. It was a sort of natural outgrowth of the writing.

I thought it was funny at the very, very beginning: the young monk, Martin, survives by basically climbing into the lavatory pit and literally sitting in the shit while everyone else is killed. He’s deeply ashamed of this. He just got scared; he was young and he survived because he’s a coward, and so he’s terribly ashamed of this and he wants to make it up to God by rebuilding the monastery single-handed, which is, of course, a ludicrous task. I thought his discussions with my guy, Grimur the Viking, could be really funny because both sides would be so strange to each other. It just made me laugh to think of: how would they speak to each other? How would they help each other when their worldviews were so different?

You know, I’m in my 50s. I’m not the usual age for a debut novelist, and I always get annoyed when I read books or watch films where the action hero is never tired. They’re never just old blokes. I thought it would be funny, because that’s a hard life, being a Viking. A lot of rowing, and a lot of fighting. I used to be quite fit, but when I go running, I’m just like, “Ah, I’m out of breath,” and all the young guys are up ahead of me in the club. I thought it would be funny to have him jumping off the boat with his sword and everything and then all the other young Vikings are running off, and he’s like “Oh, dear me. I can’t keep up with these young men,” huffing and puffing. He’s wondering, is he going to be out of breath. When he gets there, is he going to have to do some really hard fighting? I just like the idea of a slightly grumpy, tired old man being a viper.

JC: They struck me almost like a team of professional athletes. This is where we got to gear up for the game. Go in, beat the other team, get out again. Grimur is close to retirement.

DG: One of the things I love about the novel form is that you can borrow from movies, but sort of get under the skin. I wanted to play with that, but at the same time, have the pleasure of being able to get inside the characters’ heads and the dumb assumptions that they have. Poor old Martin falls in love with this girl who arrives on the island. He’s just a silly teenage boy in love and mixing that with his very, very serious study of the Bible is also funny for me.

JC: The language that you used in the book was wonderful. Occasionally lyrical, often earthy in the dialog, in the description, the vocabulary felt like it was drawn from that period, the Gaelic, Norse, Anglo-Saxon, Celtic, what have you. How did you achieve that effect? Did you research it? Did you read other books from that period?

DG: There are a few different things. I never directly research, as such. Usually, what happens is, there comes a point in where I go, “Oh, yeah, all those books I’ve been reading — that’s a novel!” It was a bit like that with this. I was very, very interested in medieval Scotland, so I was reading all kinds of things. I was reading medieval histories. I was reading Gaelic, translations of early Gaelic hymns, poetry, all kinds of stuff like that. I was quite familiar with that language.

I was becoming very interested in Viking and Norse stuff, and reading all about that. I discovered these fantastic things called kennings. A kenning is a poetry form that the Norse used, which has really quite elaborate metaphors; metaphors with two steps in them. For example, if I said I’m setting out on the “Whale Road”, the “Whale Road” is the sea. One of the strangest ones is the “gold on the branch.” It means a ring, but the ring is on a woman’s arm, so [it indicates] a beautiful woman or a rich woman.

There are lists of about a thousand of these kennings — these phrases that get used — that a Viking would know, but they’re deliberately odd and strange. That was a real treat for me, because I just thought, “Well, whenever I’m stuck, I’ll use one of them, because it’ll make things interesting” because it’s just such an odd way to see the world. I used quite a few kennings.

There’s a type of thing that happens, for example, in The Lord of the Rings a character says, “Long have I yearned to see the tower of Minas Tirith.” I always think that’s nonsense. Nobody speaks like that. Nobody speaks like that now, but they didn’t speak like that. People in the old days didn’t talk like that.

JC: It’s not portentous.

DG: Yeah!

JC: The first thing they would have said is, “Holy crap!”

DG: Exactly. I always think they should say, “Oh God, I’m really knackered. I just fought a big battle, and do we have to climb that? Oh no!” Maybe that’s where the humor comes from. I think pomposity — whether it’s the pomposity of how we view Vikings or the pomposity of how we view early Christians — is probably where the comedy comes from.

JC: That was one of my favorite things about the book, it felt lived in and it naturalistic, even though it was foreign, with obviously different ways of life and different mindsets. Those were people doing the best they could, and trying to be as happy as they could in the environment in which they live.

DG: Right. One thing that I absolutely know about a Viking like Grimur: he was a human, and because he was a human, he felt the wind on his skin, he felt thirst, he had emotions. He felt love and desire and all of these things. I know that, so I know he was like me, but I also know that he was utterly strange to me and had thoughts and did things that I could never understand.

That tension is really interesting for a writer; you try to find the ways where they’re like you, but you also try to remember where they’re really different from you, and that tension is quite fun to write into.

JC: We’ve mentioned more than once that this is your first novel and that you have an established career as a playwright. I saw something where you once said that you were “jealous of people who’d written a proper book.” What made you decide to put yourself in that group?

DG: The first thing is true, I still think playwrights aren’t really writers. I think we’re hacks, we’re terrible old hacks. We’re craft people, really.

Scottish people don’t really like theater. The Irish people, they know about theater and plays, and the English do. But Scotland, basically because we had a Protestant Revolution, we just banned theater for four hundred years. We didn’t have theater or music. So, theater in Scotland is a little bit of a suspect tradition, a little bit like you run a brothel or something. Whereas the Book, yes, well, that is proper because at the very least it’s written in language. It’s a book! You can hold it. It’s work if you’ve done a book.

All my life, I had wanted to do a book, but every time I sat down to do it, I would write just the most awful rubbish, because I was trying to be clever and important. I would sit and say, “Oh, I should write my book today.” I would sit down, and the sentence would be: “David Important stood and looked out of the window at the terrible world and wondered where it had all gone wrong.” Oh, God, it was so boring.

I gave up until the editor of a series called Darkland Tales said he wanted to commission a series of short thriller novellas set in some part of Scottish history, by authors who had some audience and sell them to partly a Scottish public, with the awareness that there are people who travel to Scotland and might want to know about Mary Queen of Scots or Bonnie Prince Charlie.

He’d done a few of those. They’re very, very good, and I admired them and the writers who did them. He then came to me. I don’t know how he got hold of me, I mean, I’m a playwright! Someone had said to him that I liked history, so he said, “Would you be interested in writing a short thriller set in Scottish history?”

That was a huge door opening for me, because suddenly I was slightly back to being a hack again, if that makes sense. I wasn’t sitting down to write the great Scottish novel and then failing because it was so stupid. In fact, I was now sitting down to write an exciting story set in the past, both of which I liked. It was odd. For the first time, I was writing something that I might actually want to read, and it had never occurred to me that that was something that you could do. I thought novels had to be slightly boring and difficult.

JC: That is one of best pieces of advice I’ve heard from more than one writing instructor, to write the book you want to read.

DG: But it’s incredibly hard, isn’t it? Because as people, we’re so interested in what people think of us, and we have illusions of ourselves and we want to live up to those illusions. So, you’re terribly disappointed when you realize that you’re a comic novelist and you’re not going to ever be the Dostoevsky that you wish to be. But it’s also a great liberation when that finally happens.

I don’t know if you know the story about Martin Amis and his father, Kingsley. Martin, obviously the great novelist of the ‘80s and ‘90s, and Kingsley, a British comic novelist in the ‘50s. Martin was always very upset that Kingsley didn’t read his books. One day, he challenged his father on this, and his father said, “Oh God, Martin, you know me. I can only read a book if it begins ‘A shot rang out.’” Clearly, Martin’s big, pretentious tomes didn’t have that.

I always loved that story, because I’m a bit like that myself. I would love to begin with “A shot rang out.” In a way, with The Book of I, that’s as close as I can get for a Viking story to begin with “A shot rang out.” We get catapulted head first into the raid.

JC: Well, this “potboiler” has a good deal to say about the human condition and other important things in life. It’s also very fun.

DG: I’m so happy you say that. I genuinely believe that it’s one of the great mysteries of life. If I’d sat down to say, “David, what do you think about the human condition?” I would have written rubbish. But because I sat down to say, “Let’s do an exciting story in which a Viking has to survive for the summer in hostile territory,” oddly, then, out of that comes things.

I didn’t mean to do it but I’m pleased you noticed that. I’m not very good at writing thrillers. The truth is, part of the reason the whole thing works, is because I couldn’t really do a thriller. I just think it’s funny. I just keep thinking it’s too funny. The attempt to do something that I can’t really do actually helped me in a strange way.

JC: I think people are really going to enjoy it, and I am looking forward to introducing it to people. I hope that the Indies Introduce program introduces it to a lot more people. It’s been wonderful to talk to you, thanks for being here!

DG: Could I just briefly say, to you and the people listening — many of whom are indie booksellers — I just think you are the noblest people on earth. I grew up going to independent bookshops at a time when every town had an independent bookshop, and there were no great chains and no mighty internet dominating everything. When I find an independent bookshop, the curation, the care, the love of the book, in a world that seems to be shedding all of that, I love it.

The idea that independent booksellers have picked my book means a great deal to me. It candidly means much more to me than had it been some algorithmical win on the great lottery of Bezos.

Thank you very, very much for having me and for picking the book. I’m really thrilled about it.

JC: Long have we yearned to hear that from you.

DG: That’s really good! Thank you very much.

The Book of I by David Greig (Europa Editions, 9798889661276, Hardcover, Historical Fiction, $24, On Sale: 9/9/2025)

ABA member stores are invited to use this interview or any others in our series of Q&As with Indies Introduce debut authors in newsletters and social media and in online and in-store promotions. Please let us know if you do.

Source link