Gilbert’s new memoir is bonkers yet transcendent

Elizabeth Gilbert’s latest memoir, “All the Way to the River: Love, Loss and Liberation,” is a blockbuster: absolutely bonkers and right on the money; brutally honest, including about what it conceals; lurid, transcendent, and compelling. That said, whether readers enjoy it or even pick it up may depend upon their tolerance for its copious visitations from dead lovers and their mothers, dialogues with God, mediocre poems, lectures on codependence, and doodles with inspirational slogans, not to mention the author herself.

Gilbert is undoubtedly a force, but at this point it’s hard to know how and where to categorize her. Over the years, she has made a name for herself as a journalist, self-help guru, novelist, creativity maven, advocate for Black women writers, and influencer, piling up bestsellers and social media followers along the way. But across all her seeking and creating, uplifting and supporting, navel gazing and attention seeking, she is first and foremost a writer who excels at observing and chronicling individual experience, even if she sometimes walks a fine line between triumph and treacle.

Those who don’t know Gilbert by name likely still know her breakout memoir, “Eat, Pray, Love,” which brought her fame, fortune, and Julia Roberts as star of the movie. Literary gossip aficionados may know that in April 2016, she left the husband she met at the end of “Eat, Pray, Love,” the man who inspired her second memoir, “Committed: A Love Story,” for her best friend of over a decade, Rayya Elias.

A friend of Gilbert’s once described Elias — an East-Village-by-way-of-Detroit hairdresser, punk rocker, ex-addict, and author of her own memoir, “Harley Loco” — as “the love of Liz’s life.” But Gilbert only acknowledged she was in love with her friend when Elias was diagnosed with advanced liver and pancreatic cancer and given six months to live. In short order, Gilbert exited her marriage and declared her love. Elias’s response? “Why did you take so long to come to me?” and “Let’s just live balls to the walls until I die.” Which they did, until it got complicated, then horrendous (to the point that Gilbert “came very close to premeditatedly and cold-bloodedly murdering my partner” with fentanyl patches), and finally briefly beatific.

Gilbert’s unsparing anatomy of “the truth about what happened between me and Rayya Elias — our friendship, our romance, our beauty, rage, and pain … Rayya’s addiction, her relapse, and her death” is beautifully constructed, eloquent, funny, horrifying, self-aware, scrupulous, and gripping. Though the first chapter forecasts the arc of what she believed would be their “once-in-a-million love story,” its glory is in the details.

Litany, a central rhetorical motif surely intended to evoke prayer, is one vehicle for detail: Elias was “An unfailingly honest master manipulator. A fierce protector who always had somebody taking care of her. A needy alpha who demanded solitude but could not bear to be alone.” Another is the book’s narrative acuity (solemn and profane), which reaches its peak in the weeks that Elias finally lies dying in Detroit: as her ex-girlfriend, ex-wife, and Gilbert kept vigil, “Outside, the light was changing. A gray dawn was coming, and with it more snow. … It felt like a change was happening in the room. A deepening silence, a deepening presence. And that’s when Rayya opened her eyes and said in her regular voice, ‘What are you guys doing?’”

You may have noticed that this book is Gilbert’s third memoir with “Love” in its title. But this iteration of her story is notable for its ultimate rejection of romantic love. In the wake of Elias’s death, Gilbert comes to terms with her realization that she is a sex and love addict — and with the role she played in the chaos of what she comes to see as a long-term relationship between two addicts.

Gilbert grounds her at once empathetic and sharp-eyed account of addiction, codependency, recovery, relapse, and “a power greater than myself” in the notions that “love addiction is at the bottom of all the other addictions,” and childhood trauma is at the root of love addiction: “Of all the human desires, the need to feel loved is the most fundamental. When unmet or perverted at a tender age, that need can warp our brains into making dangerous and even insane decisions for the rest of our lives.” It’s a seductive narrative, especially for a book written not just to understand her own life but to help “anyone who might need it.” Yet it simplifies the current understanding of addiction, even as it casts a perhaps alarmingly wide net.

That said, it certainly works for Gilbert. The recovery community teaches her to stop pouring her unquenchable desire for love and control into other people (a leitmotif of her previous memoirs) and instead love and protect herself and her 5-year-old inner child, Lizzy (yup, there’s an inner child). By the end of the book, she has achieved happy, peaceful sobriety (at least until her next memoir).

Writing on serial memoirists, Henry Alford distinguishes between “those who simply want to capture life as they themselves experienced it, and who happen to have more than a book’s worth of material; and those for whom an additional memoir or memoirs is a form of repudiation or correction.” Gilbert is both and more, lacing her memoir mix with big dollops of self-help, spirituality, and influence.

Does she go over the top? Sure. Does she do it well? Undoubtedly. Is she endlessly “balls to the wall” in her own special way? Absolutely. After all, she is Elizabeth Gilbert.

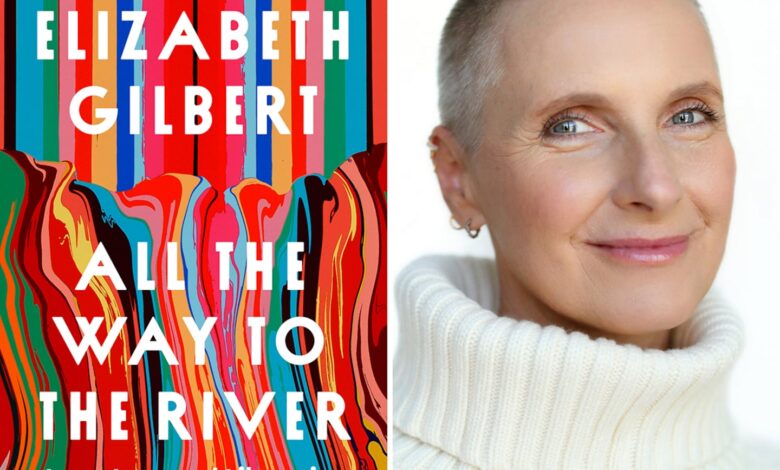

ALL THE WAY TO THE RIVER: Love, Loss, and Liberation

By Elizabeth Gilbert

Riverhead, 400 pages, $35

Rebecca Steinitz is the author of “Time, Space, and Gender in the Nineteenth-Century British Diary” and writes a weekly newsletter at https://notquitesureredux.substack.com/.