Gary Shteyngart’s new novel offers a dystopian America that feels familiar

Reading a political novel set in the near future can generate a chill in me that I find harder to shake than the gut punch of a wholly dystopian tale.

The superpower of a near-future novel is its familiarity.

As riveting as the terrors unleashed in novels like Peter Lynch’s “Prophet Song” or Margaret Atwood’s “The Handmaid’s Tale” are, the extreme nature of the political horror can ironically offer some comfort — even a false comfort — in its strangeness and its distance from now.

What can be harder to dismiss are big, thumping warning signs that emerge in a nation so similar to present day.

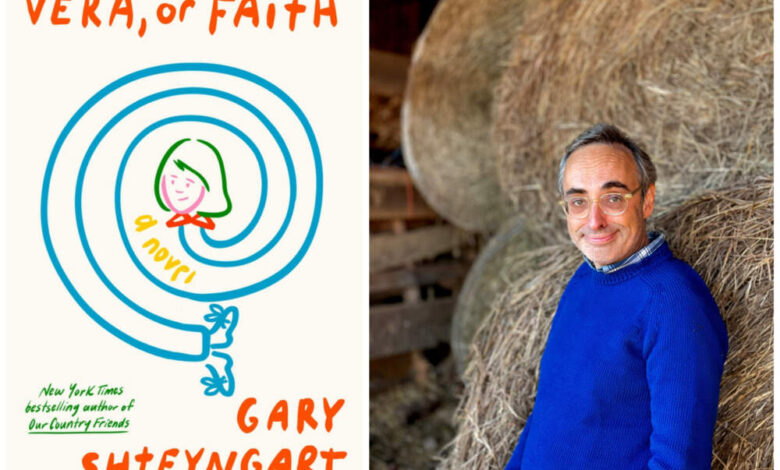

Gary Shteyngart’s sixth novel, “Vera, or Faith,” is a family drama set in an America on a slow slide toward totalitarianism, written with his distinctive blend of buoyant satire and bruise-your-heart poignancy.

The America of this novel is somewhere between the Trump-driven agitation of 2016 America Shteyngart depicted in “Lake Success” and a future authoritarian America in his “Super Sad True Love Story.”

The entire narrative is delivered by Vera Bradford-Shmulkin, a bright and endearingly anxious 10-year-old. Vera easily reads at a ninth-grade level but finds the social subtleties of fifth grade daunting. Shteyngart underscores her earnest outlook by starting each chapter title with “She Had To…” As in: “She Had to Hold the Family Together” or “She Had to Survive Recess.”

Vera is half Russian on her father’s side and half Korean from her biological mother, whom she has never met but wonders about often. She thinks of her biological mom as Mom Mom and calls her stepmom, who is the only mother she has ever known, Anne Mom. Her father is simply Daddy.

Words and what they signify are important to Vera, and to this story. To better understand the world, she keeps a “Things I Still Need to Know Diary” in which she notes all the grown-up terms she hears, like “nondescript” and “playing the long game” and “code switch.”

Because Shteyngart lands one beautifully crafted phrase after another, you’re both entertained by and made very aware of how mysterious adult argot can be to children. The Orwellian distortion of language by the current political group in power is also made disturbingly clear. It’s fitting that this plucky protagonist’s name can mean faith or truth.

Set primarily in New York City, everyday life in this novel looks very much like today, except for a deeper AI presence and some pernicious new laws.

The government now monitors the health of women who live in or travel through states where abortion is illegal. When entering or exiting a “Cycle-Through” state, a woman must submit to a test to determine where she is in her menstrual cycle and whether or not she is pregnant; results are uploaded to a national tracking database. In 2025, this reads as alarmingly plausible.

Of course, no dystopian novel would be complete without a majority group feeling resentful and downtrodden. A proposed constitutional amendment seeks to turn the 1787 Three-Fifths Compromise upside down. If passed, the “5/3” vote would bestow five thirds of a vote to each “exceptional American” — a descendant of the white people who settled here “before or during the Revolutionary War” and who now fear their prospects are endangered by minorities. It’s such a charged issue that Vera’s fifth-grade teacher has the class stage a debate about it.

In barbed comic passages, Shteyngart tempers the humor enough to show how vast swaths of the citizenry now accept as normal what once would have been considered dangerously extreme.

Still, most of this tenderly charming novel is Vera puzzling out the ever-changing dynamics of school and home. How to make a real friend at school? Why did Mom Mom leave? Why won’t Daddy and Anne Mom talk about her? How to hold the attention of one parent or the other? This last one is an especially steep climb.

As in previous novels, Shteyngart gets flawed parenting painfully right. On a scale of awful to wonderful, Vera’s parents are just self-absorbed. Her Boston Brahmin stepmom and her Jewish Russian immigrant father clash — loudly — on a variety of topics, from politics to the cost of living in New York City to, already, the college their two elementary-school kids should attend. Vera can’t help but soak up tension from the worrisome ideas that leach from her parents’ unfiltered arguments.

The entity that Vera is most comfortable with is her AI-powered chess computer she named Kaspie and with whom she often has more real conversations than she does with either parent. Kaspie truly listens to her questions and provides thoughtful answers.

Although she is more drawn to her free-wheeling father, it’s Anne Mom who emerges as more attuned to Vera, offering gentle advice on how to communicate with her classmates (like not using words like “exquisite” and “delectable”).

Meanwhile, below the surface of everyday life, changes begin to swell and roll.

Vera’s father, the editor of a floundering academic magazine, has been indulging even more regularly in his beloved martinis as he tries to keep the magazine solvent. In this new Russia-friendly political environment, will his sometimes-faulty moral compass keep him on the straight and narrow or steer him toward a ruinous financial solution?

Vera’s stepmom is busier than ever organizing against the 5/3 vote. And Vera is more determined than ever to solve the mystery of her birth mom. Whatever it takes.

“Vera, or Faith” is barely more than 250 pages. Shteyngart did not need more than a slip of a novel to create a spirited young girl courageously moving forward through a world that is completely believable in its absurdity.

Hosted by Harvard Book Store, Gary Shteyngart will discuss “Vera, or Faith” with Tom Perrotta at the Brattle Theatre on Thursday, July 24.

Source link