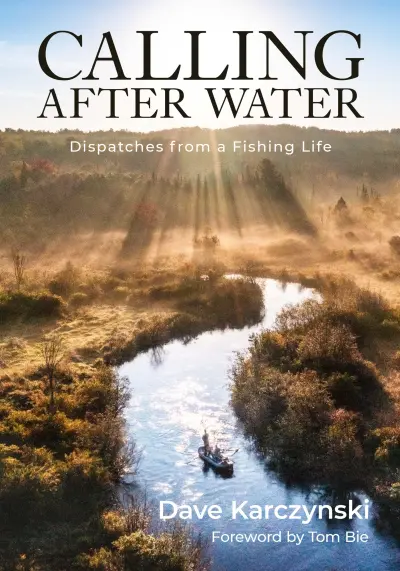

From Wilderness to Family: Karczynski’s Path

Author Dave Karczynski on fly fishing, chasing passion, writing and staying still.

Dave Karczynski’s new book, Calling After Water, spans decades and distances. The essays drift through rivers in Patagonia, the Himalayas, Poland. But no matter how far they go, the stories still carry the voice of someone who grew up close to home—fishing northern Wisconsin, wandering the Upper Peninsula, coming of age in Midwestern water. Now a lecturer in creative writing at the University of Michigan, Karczynski has spent the last couple decades chasing fish, chasing meaning, and these days, chasing a 3-year-old around his family’s Michigan farm. The book tracks years of travel—from solo trips and strange countries to something quieter, steadier. But it’s not just about fishing. It’s about what happens when you give years to something you love, and then learn how to let go of it—at least a little. We talked with Karczynski about wonder, travel, self-mythology and what changes when a person finally decides to stay put.

You’ve fished the same water that Hemingway wrote about, but you don’t really play into that. Were you ever tempted to lean into the legend—or does that whole thing just feel worn out?

I am a Hemingway devotee, having read everything, and I mean everything—the conventional canon, the posthumously published stuff, the biographies, the literary criticism. Were I asked to send something in a capsule to alien planets to teach them about human civilization, I’d throw in Big Two-Hearted River as humanity’s purest representation of the sporting arts. That said, I don’t feel like dropping Hemingway’s name into an essay serves the essay. But I do have my subtle nods. Now I Lay Me shares a title with one of my favorite Nick Adams stories. And in A Hex Upon Me, I drop the line, “I felt all the old feeling,” which is cribbed from Big Two-Hearted River as a kind of subtle homage.

There’s always a line between writing about fishing and turning yourself into the main character. How do you know when you’re slipping into self-mythology? Or do you just try not to overthink it?

I’ve got what I call the schmuck test. If I read something back and the guy on the page feels like a schmuck—or like someone trying too hard to sound like he’s figured it all out—I either rewrite it or cut it loose. A few essays didn’t make the book for that exact reason. Some had been written years earlier for magazines with totally different audiences, and when I looked at them with fresh eyes, they just didn’t sit right anymore. You do have to make yourself into a character in this kind of writing, but the trick is not to mischaracterize yourself. I try to ask, “Is that really true?” That’s the gut check.

RELATED READ: Experience the Hex Hatch in Northern Michigan—It’s Epic

You’ve spent years chasing fish across oceans and time zones. Looking back, do you think that was about wonder—or was it also a way to avoid stuff back home?

It was about wonder, for sure. Each trip, and especially during the first half of my travel career, when it was fresh and sparkling and new, was absolutely awe-inspiring and magical. Fly fishing as a sport has done a pretty good job of finding angling opportunity in the most enchanting parts of the world. And as much as I traveled, there was also considerable down time that came as a result of my job. The academic schedule is definitely a different kind of life. You’re off, with pay, for five months a year, and even when you’re working, it’s only for two days a week, and then just for a few hours a day. So if you are unmarried, no mortgage, no child—which I was during my traveling days—you are almost fatally awash in free time. I’m grateful that fly fishing gave me such meaningful structure during those days. Nowadays, all life-structuring is taken care of by an indefatigable three-year-old. Every calendar day is hijinks and mischief from start to finish, and I wouldn’t have it any other way.

I can hear a few readers asking: Why do I need to read about this guy’s trip to Poland when I can walk down to the Au Sable or the Jordan and catch a trout myself ? What would you say to them? Who’s this book really for?

I’ve always tried my best to be an entertainer, and I think the reason to read travel narratives is the same reason you go to a fancy restaurant from time to time—you want to be entertained with unusual ingredients in unusual combinations. When it comes to storytelling, setting is one of your ingredients, and there’s a real opportunity for the reader to be entertained in a special way from a travel tale well executed. That said, while probably sixty percent of the book is travel, the other forty percent is squarely and lovingly set in Michigan and Wisconsin. If I never fished anywhere else besides those two places for the rest of my life, I’d be a happy man.

There’s real reverence in how you write about wild places. But was there ever a moment where fishing became a reason to pull away from the rest of your life?

I’m lucky to have come from a family of sportsmen, so being in wild places was always regarded as the very best part of life, the thing that made it special and gave it purpose. It felt more like building up and building out my family’s heritage. My wife, who is passionate about horses and trail riding, and I are doing our best to pass that torch along to our daughter. Before starting a family, we moved onto a farm so our kids could grow up hunting and horse riding and, of course, fishing. Our daughter has been tracking blood trails since before she was born and is already, at three years old, a better forager than me. So I feel like the odds are good that she’ll continue the family heritage of exploring the natural world with wide eyes and an open heart.

Let me ask this bluntly—do you think you were using fishing the way some people use, say, ultra-marathon training? Always planning the next trip, the next moment—because sitting still felt harder?

You know, it’s interesting. Any trip I took always came out of the blue, and I never knew if it was the last one or not. An editor would write and say, “I don’t suppose you have a burning desire to go to X place, do you?” So it wasn’t something I had control over or planned for, aside from the few weeks I had to get my gear in order and tie flies. That said, you’re right that I always said yes and was always very eager to decamp. I had, and have, a really hard time being in confined spaces, and life in a college town is definitely that—concrete, traffic, lots of people doing people things. Now that we live on a farm surrounded by public land about forty miles from work, it’s pretty easy to sit still. I can go into the backyard, sit in a tree with my bow and watch bucks sparring on fall mornings. I can fish and forage and get lost in a swamp on state land. If anything, it’s become too easy to sit still. I don’t think I’ve been on a plane in four years.

Fly fishing used to be this quiet thing, something kind of sacred. Now it’s branded, hashtagged and filtered to death. Do you think the soul of it still exists—or has it become too performative?

That quiet, sacred culture—which is the fly fishing culture I personally embrace—still exists, but it’s troubled. The current fly fishing culture feels like it’s just screaming at the top of its lungs at me, and I mostly plug my ears to it. Lucky for us, modern life is kind of like the beast in the children’s monster movie—it only has power over you if you believe in it. You can still leave your phone in the truck and fish like it’s 1993, or 1953. You can write essays instead of making TikTok videos.

The book shifts in the final chapters where you start talking about buying a fishing property, getting married, becoming a dad. Did that shift come easily for you, or did it feel like losing something?

When I first got a peek into what “dad-ing” looked like, the hard part was realizing I couldn’t do the outdoors the way I used to. I really liked going deep—long trips, lots of planning, days at a time. That immersive, transportive experience where you’re in the river, in the weather, in the fish’s head. You’re not just fishing, you’re solving something. Predicting hatches. Cracking a code. That kind of experience takes four or five days. And once you’ve become encumbered—in the best way—I just couldn’t dissolve into the riffles the same way anymore. Now, instead of that long stretch, it’s more about quality. Concentrated time with friends. Fishing rivers I really know, close to home. But it’s been replaced by other types of things that bring the same joy. Our little farm. The family life. And that endorphin hit after endorphin hit watching my daughter run around and grow.

RELATED READ: Waters of Enchantment: Go Fly Fishing at Wilderness State Park

Writing about travel always comes with a little ego—this idea that your experience matters enough to share. How do you keep that in check, or do you just lean into it?

I try to freight every narrative with an interesting driving question that I wrangle with as the essay unfolds, so that it has a purpose beyond simply relaying an experience. This is also how I teach the essay form to my students, that it has two very distinct components. The first is what happens. The second is what the essay is about. Without the latter, most travel tales would get boring fast.

Last one: Who was braver—the guy who flew to the Himalayas to fish, or the guy who stayed home and tried to build a life?

Great question. You know it’s funny but going to the Himalayas and starting a family both felt like the easiest and most natural decisions in the world in their respective moments. I’ve always been pretty good about listening to myself and doing what the mind and soul need at a given time. There was a time when I needed to be on the water 150 days a year to function correctly. Now I fish five and that feels like more than enough. The most exciting trip I have on the offing is my daughter’s first bluegill excursion to a local lake. Instead of packing rods and reels and camera cases and fly boxes, I’ll have a can of worms and a jar of pebbles to throw, to keep my daughter busy. Maybe two jars. And I can’t wait.

Bob Butz is a magazine writer, book author and essayist whose work has appeared in every major outdoor magazine as well as The New York Times, GQ, Sports Illustrated, Men’s Journal and many others.

Source link