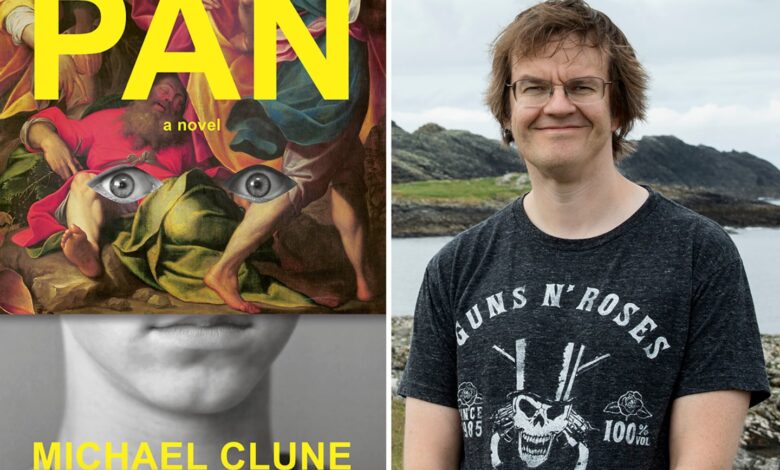

Book review: ‘Pan,’ Clune’s debut novel

In his 2013 addiction memoir “White Out,” Michael Clune writes that his first word as a child was “clock” — a perfect verbal origin story given that his writing examines, with obsessive attention, our experience of time. The real appeal of heroin is temporal in nature, Clune argues in that book: dope obliterates the difference between now and then, clearing away the encrustations of ordinary perception and allowing the user to live in a perpetual present. “Pick up a white top,” he writes, “it’s like picking up a white phone, and the angel of the first time is singing down the line.” When considering how the present seems swallowed up by past and future, Clune sounds like Augustine: “At every instant the addict inhabits at least two times at once: the first time he did it and the next time he will do it. Right now is the switchboard.” When exploring the power of repetition in “Gamelife” (2015), he reads like William James: “Everything that happens in a computer game happens ten thousand times. Because computer games mimic habit, they get through to us.” Always, Clune is interested in what he has described as “the raw stuff of time itself.”

After two memoirs and two academic monographs, Clune now has a novel, “Pan.” His narrator, Nick, is 15 and living with his divorced father in a crummy subdivision of a distant Chicago suburb, circa 1990. (The details of subdivision life are spot-on, from the faux-classy name, Chariot Courts, to the nights spent eating microwave lasagna and watching “Head of the Class.”) Time is particularly taffy-like during high school — has the clock ever moved so slowly as during your first summer job or so quickly as during the August nights just before school starts? — and Clune nicely gets at the odd rhythms of teenage existence. Nick worries over being cool for years and then finds himself popular and unhappy about it. He spends a semester not speaking to his crush only to commune suddenly with her over Boston’s “More Than a Feeling.”

All of this makes Clune sound like Jonathan Franzen, a cartographer of Midwestern schools and suburbs. But if “Pan” is a work of realism — and that’s an open and interesting question — then it’s interested primarily not in the realities of social existence (what it’s like to live in a particular time and place) but in the realities of consciousness (what it’s like to think in a particular way). Early in “Pan,” Nick starts having what he comes to understand are panic attacks. Sitting in geometry class, he realizes that his hand is a thing, just like the textbook and eraser he sees in front of him: “That’s when I forgot how to breathe.” Soon after, he’s watching “The Godfather III” when he forgets “how to move blood through [his] body.” He begins worrying that, if he stares at something or someone too long, his “looking,” or his “thinking,” or his very self (it’s hard to tell them apart), will escape from his head and stick to what he’s staring at.

How does subjectivity, the ineffable feeling of being a person, arise from the material brain and its measurable neural firings? How is it that thinking takes place within time and yet seems to remove us from time? (There’s Augustine again.) Think too much about thinking and these questions, and you, start falling apart. Nick is “a pragmatist” (there’s William James again), and “Pan” follows the strategies he develops to deal with his panic and insomnia: note the symptoms that precipitate an attack; breathe into a paper bag; meditate.

Interwoven with this rather straightforward, if effective, story of mental health and its treatment is a wilder, stronger strand. Nick hooks up with a group of cool — read: trouble-maker — friends. They start hanging out in a family barn they call, with equal parts irony and mythic seriousness, the Barn. There, they do drugs (Nick doesn’t; he’s read they can trigger panic attacks), listen to music, engage in rituals (dancing, more drugs, sex), and decide that Nick has been inhabited by the Greek god Pan. As Ian, the group’s ringleader, declares, “When you are aware of the panic, you are seeing the truth of ordinary life” with “absolute clarity.” Panic isn’t a condition to be managed; it’s a divine possession to be embraced. It shows us the truths — the subject is an object; selves are porous to one another; “time was part of the body after all” — that we normally refuse to see.

Nick is regularly described as being “loose,” ready at any moment to drift from his mind and the world. “Pan” is, in many ways, a loose novel. It refuses to be one thing or the other; its plot moves — Nick tries out new ways of controlling panic; his friends come up with wilder theories about panic’s sacredness — but at its own strange pace. Is the claim that Pan is real and within Nick meant to be taken literally? Or is it a metaphor to describe how we are visited by thoughts that seem beyond us? Yes and yes. Clune doesn’t choose between what we might describe as the poetic and the novelistic, the mystic and the naturalistic, explanations of Nick’s experience. When it comes to time and consciousness, Clune’s perennial topics, visionary perception is perhaps just a deeper form of realism.

Anthony Domestico is an associate professor of literature at Purchase College, SUNY, and the books columnist for Commonweal. His reviews have appeared in The Atlantic, The Baffler, The Washington Post, and elsewhere.

PAN

By Michael Clune

Penguin Press, 336 pages, $29