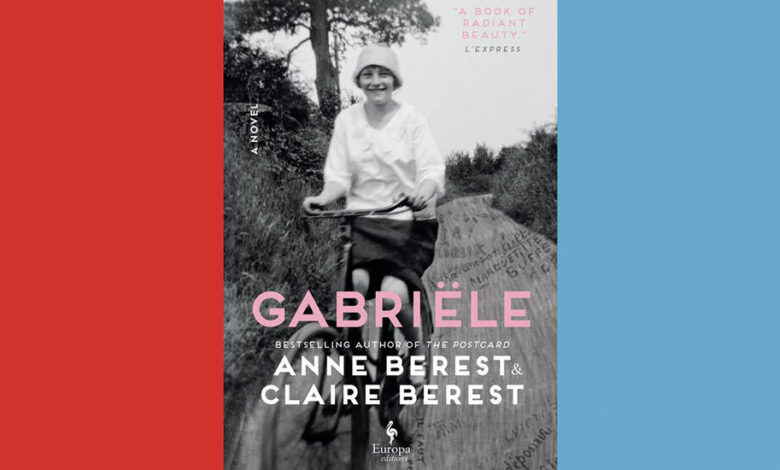

Book Review: ‘Gabriele,’ by Anne Berest and Claire Berest

In the south, Gabriële has her first sexual experience with a lover who, in the morning, confesses that he lives with his longtime mistress, and asks her to wait while he drives to Paris to end things. Gabriële, so modern and independent, finds herself “turned into a disheveled, two-bit Ariadne deserted on the beach by her Theseus.” But within a few months, the couple are married, and Gabriële never composes music again. Instead, she devotes her life to midwifing the talent of others. Her husband’s name, Francis Picabia, will soon become known around the world.

In Paris, Picabia takes drugs and paints while Gabriële watches, gestating a baby and a new vision of painting. In 1909 he produces “Rubber,” one of the first truly “abstract” paintings in art history. Then it’s a sprint: Cubism (and its internal fights), fame in America at the Armory Show, the outbreak of war, the stirrings of Dada. Friends become household names, like the handsome young man with the “spare, crescent-moon profile,” who will join the Picabias in an intense, unconsummated threesome — Marcel Duchamp. The list goes on: Igor Stravinsky, Guillaume Apollinaire, Isadora Duncan, Elsa Schiaparelli and the other Spanish Pica — Francis’ nemesis, Picasso.

The Picabias produce four children — girl, boy, girl, boy — between 1910 and the end of the marriage in 1919: the “arbitrary hostages of a pair of monsters.” The last boy, the authors’ grandfather, was delivered at home with Duchamp acting as midwife. When this son died by suicide at 27, he left behind a 4-year-old daughter, Lélia, the authors’ mother. The Picabias were still alive, but utterly indifferent to their family; they “never put their arms around the living child of their dead child.”

“Gabriële” arrives at a moment of reckoning with the position of women in the history of art, and fascination with the female “art monster” who abandons family for craft. In several asides to the reader, the authors share their qualms about the project, including what one friend describes as their attempt to put a “‘feminist’ sheen” on the life of a woman who denied her own creativity to foster men’s careers.

Yet through the sheer vivacity of the character, who makes her (sometimes shocking) choices freely, we are able to consider a more complicated story than the dichotomy of abused muse or neglected genius. Like Gabriële herself, this book takes on big ideas about modern art and modern life — without losing sight of the people caught and crushed in those turning gears.

Source link