A Trapdoor of Her Own

Emmeline Clein considers girls, games, and heterosexual monogamy in her review of Sally Rooney’s new novel, “Intermezzo.”

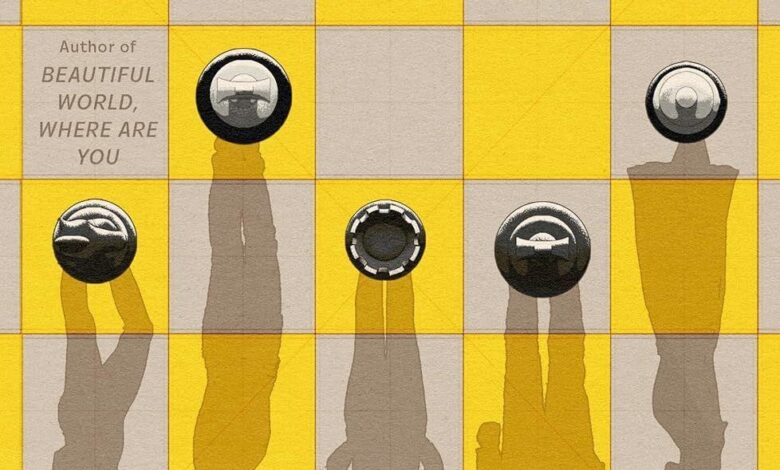

Intermezzo by Sally Rooney. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2024. 464 pages.

A MAN WITH a Xanax problem, a recovered incel, a divorcée, a giggly undergrad with an active OnlyFans, and a slender university professor are playing a game. Multiple, actually—sexual brinkmanship, financial foreplay, literal chess, political pissing matches, linguistic swordplay. Death drives whir in the background; there is bluffing by all parties.

Seven months before the release of Intermezzo, a Goodreads user rated the book five stars and posted the following comment: “this is the most exciting news of my year and i got engaged the week it was announced.” This “review” had over 2,000 likes the last time I checked—and seems as good a jumping-off point as we’re going to get for the Rooneyverse, a sea driven by swelling tides of hetero-optimism, and one critics have been extraordinarily eager to dive into. The question is, are we diving into an infinity pool, or shark-infested waters? In much recent literature written by white women who are not Sally Rooney, heterosexual romance resembles the latter. But while the heteropessimists were busy penning aggrieved, wrathful yarns narrating their exits from marriages understood as microcosms of misogynistic superstructures, the sexy, sarcasm-drenched girlfriends of Intermezzo were unionizing—not to mention fucking.

Like all good games, Rooney’s previous novels have rules. Allow me to enumerate these. I apologize in advance for the digression; this new book is around 200 pages longer than was ultimately called for, though, so permit me a few extra paragraphs.

Normally—and more on that word in a moment—a Rooney novel runs on yearning, miscommunication, wry flirtation, and earnest if slightly too stylish effusions of never-acted-upon leftism. To date as a young adult in these novels is to play an artificially dangerous game of its own, one in which the stakes are low and the suicidal ideation quotient is alarmingly high—a ratio that’s likely not unrelatable to readers in the milieu Rooney is either satirizing or servicing, depending on your angle.

In Rooney novels, slender, smart, amorphously sad girls stumble into relationships with sweet, equally intellectual men who save these girls from their own self-hatred via very trad sex during and after a series of highly avoidable misunderstandings. The throbbing, internally directed loathing afflicting such “small,” “frail,” “thin,” “slender” women is never really explained beyond oblique, obfuscating gestures at some sort of inherent wrongness—an almost religiously infused sense of original sin. Frances of Conversations with Friends (2017) considers herself a “damaged person who deserve[s] nothing,” her “body […] an item of garbage,” even as she earns academic accolades, publishes her first short story in a literary magazine seemingly effortlessly, and is pursued by various love interests. In Normal People (2019), Marianne—“a very gifted writer” with multitudes of admirers at university—understands herself as “a bad person, corrupted, wrong”; a woman whose “efforts to be right, to have the right opinions […] only disguise what is buried inside her, the evil part of herself.” And so on and so forth with the protagonists of Beautiful World, Where Are You (2021), Eileen and Alice, the former feeling like “God is punishing [her]” and the latter that she is a “terrible” person.

In Rooney novels, the girls are guilty. This raises the question: Of what? They work at arts organizations or literary magazines; they attend university and, as friends to each other, seem relatively decent; they hold the “right” opinions and voice them, ardently, at every opportunity, though, admittedly, these come more often at cocktail parties than at protests. (Rooney herself, on the other hand, continues to take very public moral and political stances, as she did at the launch of Intermezzo at the Southbank Centre in London only weeks ago.) These girls’ rhetoric primes the uninitiated reader for a dramatic trauma reveal, if not an extensive criminal record. Yet the root of their self-loathing seems to be identitarian and political, a white feminist guilt that leaves them in a headspace reminiscent of Rooney’s own collegiate mindset, as she described it for The Dublin Review in 2015: “I vacillated between a weird self-righteousness and a deceitful kind of self-deprecation.” Read a Rooney girl’s emails and you’ll find effusions of complicity in internationally entrenched systems of oppression alongside plaintive declarations that perching (daintily, pseudo-precariously) atop a racial and class hierarchy isn’t sparking much joy.

Ashamed of their arbitrary positioning in a world-historical structure of inequality, Rooney’s guilt-ridden white girls turn the vitriol they believe their identities writ large earn them on themselves specifically. In these novels, recognizing injustice and channeling that reaction into emotions that might incite actual political action is understood as naive; capitalism and patriarchy are as unshakable as they are evil, and if these girls are anything, they’re smart, they’re self- and society-aware—certain they’re seeing things clearly. Convinced they deserve to feel bad, Rooney’s girls throw themselves into forms of femininity predicated on a certain type of alluring, legible abjection. They rarely eat, they want to be hit in bed, they sob and suffer in self-effacing despair. And, as if doing penance for their privilege, they martyr themselves at the feet of the only system of subjugation ready and willing to take them: monogamous heterosexuality.

Let’s go back, for a moment, to normalcy. In Rooney novels, the trait occupies such an aspirational place in these characters’ value systems that it approaches the sacred. Alice berates herself for her inability to “live normally”; Marianne agonizes over “why [she] can’t be like” the titular “normal people” of the book in which she stars. Of course, these women understand heterosexual monogamy as “coercive,” masculinity as “oppressive,” and traditional marriage “obviously not fit for purpose.” How could they not? They’re Rooney girls. For all of their oft-criticized flaws, one can’t deny them a high degree of intelligence. Yet entering normative heterosexual relationships appears the sole salve for the “huge emptiness” with which they contend. (Becca Rothfeld has written especially incisively about the “convalescence” conferred by “normal” romance in Rooney novels, describing Marianne’s journey as one in which “at first she is broken, but then she is rehabilitated by the corrective force of Connell’s vanilla love.”)

Rooney’s public-facing, avowed Marxism has always sat at an odd angle to the matrimonial myths she weaves in her fiction. After all, heterosexual marriage is a basic unit of capitalism. The novelist’s solution is a subtle sleight of hand: where egalitarianism might have found a foothold, hetero-optimistic normalcy steps in. Perhaps adhering to normative, heterosexually monogamous standards is imagined as a move toward equality by these girls, an individuality-effacing effort to simply escape the pedestal they were born on—remember, these are women who know that meritocracy is an “evil” fiction—rather than complain about the pain incited by their plinth and its place in an oppressive superstructure, or try to knock it down entirely. Playing monogamous partner to a man can catapult a woman with the potential to be mistaken for a girlboss with means into a pseudo-proletariat of submissive girlfriends. But solidarity with whom? Enclosed in their normative dyads, Rooney girls are relieved of the pressure of agency. Blinded by heterosexuality’s hall of mirrors, they mistake their own reflection for a comrade’s—but these are attempts at individual absolution, not the stirrings of revolution.

“A part of me is just like, yes, please, tell me what to do with my life,” Eileen tells her older love interest in Beautiful World, Where Are You. “It makes me feel very safe and relaxed.” This is said with a simper, of course, couched in the characteristic comedy and wry self-awareness of a Rooney girl. Still, the women’s behavior belies the joke: Eileen ends the book engaged and pregnant. The punch line is that these are girls who want to be punched—and who, beyond that, want their boyfriends to lock them into at-home recovery suites where they can lick the wounds wrought by capitalism without worrying about their role in it all.

¤

Rooney isn’t playing in a vacuum. Outside the (beautiful?) world of her novels is another one, in which the horizons for heterosexuality are also vanishing. There, though, the vibe isn’t so much that of a romantic sunset as one of a total eclipse. Over the past few years, a microgenre of divorce novels and memoirs has coalesced around the figure of the woman wounded by her marriage. From this marriage, this woman emerges bloodied, scarred—and certain. Her story is simple, almost mythic: “I married a man, as women do. My life became archetypal, a drag show of nuclear familyhood. I got enmeshed in a story that had already been told ten billion times.” These lines are pulled from another of this year’s highly anticipated novels, Sarah Manguso’s Liars, and the story they refer to ends in gaslighting, infidelity, financial and emotional distress, and divorce. It’s one in which none of the protagonist’s pain can be blamed on her own choices, and part of a growing canon in which men, serving as ventriloquists’ dummies for the patriarchy, enact clearly misogynistic betrayals on white women who, in turn, become simple vectors of victimhood—rather than participants in painful dynamics that at times are certainly caused by sexist systems and violent masculinities, yet at other times are caused by less gendered forms of interpersonal human cruelty.

In Liars, the choice to engage in a romantic relationship with a man that hurts and reduces you, if you are a woman, turns out not to be a choice at all: “[I]t isn’t a personal failure when you give in,” asserts the narrator. “You’ve been coerced.” The realization that this coercion occurred incites a conversion experience, one which offers these women a form of absolution that runs parallel to the kind offered by heterosexual relationships in Rooney novels. Instead of committing to a bit, finding freedom from agency in a chosen—albeit, to many, highly problematic—script, these writers indict the script itself, as if they were cast in these roles against their will. Of course, being thrust into a part you didn’t choose aligns with many people’s experiences of femininity. But by unquestioningly imagining women as utterly unwitting pawns to patriarchy’s invisible, ever-winning hand, aren’t we reinforcing the same submissive, naive narratives that feminism aims to point out were always the stuff of fiction?

In 2019, Asa Seresin coined the term “heteropessimism” to describe a phenomenon that “consists of performative disaffiliations with heterosexuality, usually expressed in the form of regret, embarrassment, or hopelessness about straight experience” with “a heavy focus on men as the root of the problem.” He posits that “while trying to redeem oneself from whiteness or heterosexuality through performative distancing mechanisms might seem progressive, the reality is usually little more than an abdication of responsibility.”

The divorcées exit and condemn the oppressive system, casting themselves as victims of an unshakable institution. They are innocents, “men are trash,” and agency is excised in an act that removes the narrators’ responsibility to analyze their own complicity in oppressive dynamics or attempt to change them, all the while ignoring the fact that only relatively privileged actors can make the choice to exit stage left. On the other end of the spectrum, Rooney’s self-made martyrs choose witticisms over whines or screams, mocking the subjugation inherent to heterosexual monogamy even as they play into it. In Rooney’s novels, characters consider heterosexual marriages and relationships like the most tolerable options in choose-your-own-adventure books, storylines that let female characters off the hook for making their own choices and refuse the possibility of other forms of romantic relationality. Amid the chaos of late capitalism, Rooney girls seem to prefer allying themselves with a preexisting form of suffering—one that is at least stable—over attempting to alter the oppressive contours of heterosexual romance.

It’s the long, largely untested stretch of rope between these two poles where change might be found: alternate ways of living that neither reject heterosexual monogamy wholesale nor demand a self-harming blood oath. But balancing there would be genuinely precarious, risking a fall, and above all, Rooney girls are going to be safe. If the wrathful divorcées’ victim complex entraps them in an “emotive ghetto of gender solidarity,” to borrow a phrase from Susan Faludi, Rooney girl(friend)s glibly lock themselves into cages gilded in irony, subbing in romantic “success” for sobbing or screaming alongside their sisters. By casting themselves as self-hating villains turned martyrs and winning the rat race toward marriage with a wince and a wink, Rooney girls necessarily embark on individual heroine’s journeys, seemingly understanding salvation as at odds with solidarity.

In 2017, Rooney told The Tangerine that the decline of religion, the rise of late capitalism, and what she seems to consider the emotionally sterile tenor of Marxism leave young people in a spiritual vacuum. “If you’re feeling existentially sad towards your suffering, or you want some kind of moral guidance, it doesn’t always help to read Karl Marx,” she noted. “There’s some sort of void between political theory and personal life.” The drawbridge her novels seem to be rolling out across that gulf is heterosexual, monogamous romance.

“[W]hen we tore down what confined us, what did we have in mind to replace it?” Alice wonders of heterosexual monogamy (which had, at the time of that novel’s publication in 2021, apparently been destroyed by axe-wielding feminists), observing that “it was at least a way of doing things, a way of seeing life through.” Now, Alice concludes, we have “nothing.” Maybe Rooney has seen the viral tweets declaring that “heterosexuality is a prison.” Maybe she’s offering a rebuttal, or another “way of seeing” things: sure, maybe not of doing things, but for a certain type of girl going through it under capitalist patriarchy, a prison might also be a safe house.

¤

In Intermezzo, a pair of Irish brothers lurch toward love in unexpected configurations in the immediate wake of their father’s death (the book opens with Peter’s reflections on the funeral). Peter, 33 and the older of the two, is a leftist lawyer with a substance abuse problem, an undergraduate girlfriend named Naomi who dallies in sex work and prescription drug sales, and an “age-appropriate” college ex named Sylvia who occupies an amorphous space, supportive yet fraught with uncertainty, between best friend and partner. When we meet her, Sylvia has been unable to engage in penetrative sex for the past eight years, after a never-explained accident left her with chronic pain and led her to break up with Peter. Peter’s younger brother Ivan is a chess prodigy, autism-coded but for whom a diagnosis “for some reason never seemed to be forthcoming,” fresh out of college and competing at a rural town’s local club when he meets and falls in love—for the first time—with 36-year-old Margaret.

The brothers are semi-estranged at the novel’s start, and their botched attempts at reconciliation, their feuds, and their halting grasps at friendship play out alongside each brother’s romantic pursuits, which take up far more page space than the brothers’ thoughts about either each other or their dead father. Notably, Margaret is the only woman afforded direct interiority (we receive partial chapters devoted to her consciousness). The majority of the book alternates between Peter’s fragmented, alcohol- and alprazolam-addled monologues, and Ivan’s digressive stream of consciousness. Rooney’s prose in this novel is sly, offering soft landings and harboring secrets, turning rhetorical tricks. Less sleek and more lyrical than her prior work, the book is at times entrancing, pulling the reader through the streets of Dublin at dusk with a cool, controlled hand.

The novel retains much of the hetero-optimism of Rooney’s earlier work: romance motors the characters’ spiritual healing. This time, though, Rooney admits that monogamous heterosexuality might be a bit stifling for a growing boy. Here, the women’s emotional wounds are already scabbed over; here, it’s the men who seem flayed open, in need of the validating love of various women to render their lives “real” and “worth living.” And, as usual in a Rooney novel, a so-called real and worthy life appears primarily achievable through the fulfillment of heteronormative social and romantic roles.

Peter is the more self-aware brother on this front. He is existentially embarrassed by his “disorder” of relationality: his relationship with Sylvia, once so supposedly perfect as to inspire awe and jealousy among their peers—Peter often reminisces about the two of them holding court at cocktail parties, winning debate matches with ease, and looking beautiful on their college green—has by now been “mutilated by circumstance into something illegible”; his relationship with his younger girlfriend, Naomi, represents “a kind of moral dilemma” due to a combination of its financially “exploitative” nature and his ongoing relationship with Sylvia. Legibility and narrative coherence to the traditional marriage plot—dare I say, normalcy—start out as Peter’s highest values. “Let’s get married,” he exclaims to Sylvia in a fit of fantasy, later imagining them living “the right life” together; elsewhere, he fantasizes about his other girlfriend with an “infant at her breast,” musing, “real life, that would be, yes.”

Ivan imagines himself more radical. Unlike his brother, “he doesn’t assign an idiotically high, practically moral degree of value to the concept of normality” (or so he thinks, in a rage after Peter asks him whether he thinks “a normal woman” of Margaret’s age would ever be interested in a 22-year-old). At the same time, Ivan soothes himself with the reassuring notion that Peter is wrong about Margaret, and “it so happens that Margaret is what Peter would consider normal.” On a date with Margaret, Ivan’s first time “with a woman in that way […] in front of people,” he finds that there is “a certain special feeling to it, even if no one was really looking: a feeling of self-respect.”

What women offer men in this novel is a reason to respect themselves by way of a story they can tell about their own lives—one they’ve read before, one predicated on heterosexual romance, with a happy ending they recognize. Yet unlike the female protagonists of prior Rooney novels, Intermezzo’s women enter the scene with self-respect and a tangible ability to get by emotionally and spiritually, as well as financially (while Naomi is in part supported by Peter, she responds with a “cackling laugh” when he suggests she is materially dependent on him), with or without their male love interests. While the men stumble forlornly towards normalcy, the women laugh at their lovers’ appetites for conventionally masculine legibility. “Is that the sum total of your gender identity,” Sylvia asks Peter, “you’re just desperate for everyone to respect you?”

¤

In many ways, Naomi seems like she might be Rooney’s winking answer to criticisms directed by feminists at characters like Marianne, Frances, and Eileen, who embody a femininity predicated on sadness, self-hatred, and self-harm, as well as the criticisms Rooney received over her last novel’s characters’ judgmental tone toward sex work and pornography. Naomi is self-assured and, usually, displays an almost comically good mood; she is “always laughing,” even when scrolling through DMs from men threatening to “slit [her] throat.” Peter observes that fear is “beneath her […] If it happened she would die laughing.” While he offers her additional financial security and a place to live when she is evicted, he knows she won’t wilt without him; during a brief breakup, he consoles himself with thoughts of her “survival instinct.” Unlike other Rooney girls, she has an “irrepressible love of life” accompanied by actual, physical appetite—finally, we get to see a Rooney girl eat. Naomi is depicted “pulling fried chicken apart with oily fingers,” “eating from a family-size bag of Doritos,” and “drinking sugary coffee.” Still, if Rooney is sculpting slightly new characters in Intermezzo, she’s working with the same old clay. She certainly remains attached to traditional feminine beauty standards: for all of her on-page consumption, Naomi is physically tiny, described as “adolescent-looking,” “small,” “narrow,” possessed of both a “perfect body” and “supreme desirability,” yearned for by “every man she passes.”

Sylvia, too, is repeatedly described as “slender,” “slim,” “thin”—as someone whom “everyone was in love with.” She is purified by her suffering, taking on a Christlike, sacrificial air in the wake of the accident that left her with “chronic” and “all-destroying pain,” along with, in her words, the inability to have sex “in any kind of normal way.” This exile from the all-important realm of normalcy seems to Peter “like a kind of death,” one he muses he’d rather kill himself, literally, than endure.

Crucially, though each woman knows that the other is in Peter’s life, Peter—with his obsessive fixation on normalcy—is bothered by this profusion of relations to the point of suicidal ideation. (He envisions “relief like a catch released” at the thought of his own death, freedom from the “shame” he feels over loving both women, which he understands to have “poisoned” his love of either.) Engaging with both women simultaneously drives him into a crisis of conscience and Christianity, a mental breakdown accompanied by substance abuse that the women must save him from, “unionising,” in Naomi’s (always witty) terms, to insist that he at least attempt to relate romantically to both of them. Of course, doing so would necessitate adopting a configuration that exists beyond traditional bounds. Peter expresses frantic terror at the prospect of forgoing the position of husband now or in future, a sacrifice which, to him, also means forgoing the typical distribution of power within a heterosexual dynamic. “Things like that never work in real life,” Peter tells Sylvia when she describes a dynamic that might include all three of them. “Maybe not in a conventional sense, she says. But maybe we’re not in a conventional situation.”

Naomi assertively derides Peter’s worship of normative order, arguing that he is making them all miserable “just so [he] can delude [him]self that [he’s] normal, everything is normal.” She claims that his paternalistic belief that she and Sylvia must share these values actually prevents any of them from accessing slivers of grace, sublime moments of love in a liminal form. “[T]his is actually my life,” announces Naomi, maintaining her prerogative to shape that life however she chooses. Crucially, this new storyline, this “unconventional” situation, does seem, simply, to be a throuple in which Peter gets both a Madonna and a whore—admittedly, not the stuff of family abolitionist dreams. But it’s still a detour off the highway to straightforward, strictly monogamous matrimony, a side road Rooney hasn’t taken us down recently, especially at the behest of her female characters. The novelist seems to be at least considering storylines sitting at more oblique angles to the marriage plot, perhaps attempting to launder heterosexuality’s recently maligned reputation—imagining it bending instead of breaking.

So, Peter “surveys in terror” his “proliferation of inappropriate feeling.” Nonmonogamous arrangements are, to his eyes, out of the question for anyone but “unnerving moon-faced people, the polyamorous, fetishists […] who have cashed in their erotic stake in civil society and are doomed forever after to sexual irrelevance in the eyes of anyone normal.” Where the women of prior Rooney novels might yearn for the reduction of agency and power they might find in heterosexual monogamy, Peter is paralyzed by the thought of losing the social authority conferred by future husbandhood. He fears this fate as a “social death,” even as he admits that abandoning both women to “find some nice normal girl” would be its own “kind of spiritual death.” Peter experiences heteronormative monogamy at once as an intolerable spiritual prison and an impossible-to-leave safe house, protecting him from shame as well as the vulnerability that accompanies attempting rarely scripted relations. Beyond baseline legibility, normativity also offers the promise of a higher, secure place in a social hierarchy that he hasn’t yet had to give up: in his work and politics he aligns himself with “the losers, the scorned, the unwelcome,” but as a “white, able-bodied, college-educated” man, “he has never actually had to be one of them.”

Where there are losers, there are also winners, and a game undergone. It is through the language of combative play that an escape hatch opens for Peter, a “possibility,” “another way of life.” Wordplay and rhetorical tricks turn into translations; carefully chosen metaphors can change frames of reference. Wandering Dublin’s streets, Peter remembers a line from Wittgenstein: “The decisive moment in the conjuring trick has been made, and it was the very one that we thought quite innocent.” The sentence comes from Philosophical Investigations, a treatise in which Wittgenstein lays out his theory of language games, and in which he observes that often “one thinks that one is tracing nature over and over again, and one is merely tracing round the frame through which we look at it.” When we mistake the frame for nature, when we forget that someone carved it, entrapping whatever it holds in amber, we believe to be neutral and innocent what is often ideological. Zoom out and we can see the rose-colored glasses that we didn’t realize have been tinting our gaze, the binoculars obscuring our peripheral vision.

Naomi translates Peter’s fixation on trad life into a childlike inability to withstand change: “Did you ever try to play a game with a child, and they start laying all their toys out exactly where they want them. And they’re making up all these rules, and they get annoyed if you don’t follow along. That’s you. That’s actually how you treat people.” Both admit to “playing games” in their relationship, attempting to “outwit” each other, and wanting to win. Yet, by naming the game, they can suddenly see how paltry the prize is. It is “the assortment of existing names” for relations that Peter finally recognizes as upholding the artifice he had been mistaking for “real life.” In public with Sylvia, he simultaneously fears and yearns for them “to be mistaken for what they aren’t. Or rather: to be mistaken for what they are.” Once, Peter cowered at contradiction, ashamed to be a “false true lover, the cynical idealist, the atheist at his prayers.” Yet his realization that “the name you give to a presumed relation between a man and woman may be both correct and incorrect at once […] including within itself a complex of assumptions” effectively achieves a magic trick, revealing the possibilities hidden in plain sight.

¤

All games must end. In opera, an “intermezzo” is an interlude between acts. Peter’s triangulated dynamic with Sylvia and Naomi is an “experiment bound almost certainly for one kind of failure or another, and yet attaining for these few hours and days to a miraculous success, a perfection of beauty, inexchangeable, meant not to be interpreted, meant only to be lived and nothing more.” Freed briefly, at least partially, from the now-evidently anesthetic prison of the conventional marriage plot, these characters find joy and care outside the rigid, upright walls of monogamy’s safe house. Still, this isn’t so much a new frontier as it is a vacation. In many ways, Sylvia and Naomi are stronger than girls of Rooney novels past. They are also more sacrificial. Not quite queens in pursuit of their own victories, they are ultimately pawns in the plot of Peter’s development, part of an intermission that will inevitably resolve with his life resuming its previous course. After all, “intermezzo” describes a chess strategy in which one player makes an unexpected move, demanding that the other player react, only for the first to pivot and, finally, take the expected turn.

Chess is, in fact, rife with “formulaic” strategies that, according to Ivan, you must master in order “to get to an okay position in the middle game and try to play some decent chess.” It’s in those fleeting moments of decent play—when moves aren’t predetermined, surprises stumble into existence like pieces onto unexpected squares, endgames are uncertain, and every declaration of “check” keeps players on their toes—that experience might feel flexible, relations shift, and feelings swing, breathing new air into old figurations. Life itself might be “as precious and beautiful” as this kind of chess, “if only you know how to live.”

Margaret is someone who lived according to rote tradition and ingrained routine, “contained and directe[d] by the trappings of ordinary life,” before her divorce and her subsequent entanglement with Ivan. The development surprises as much as it invigorates—amid their affair, she feels [the structure of her life] disintegrating: and yet the feeling is strangely calm,” life “slipp[ing] free of its netting,” revealing that the “thin little scaffold of respectability” and the “solid sensible ideas” she held about propriety, are “not powerful enough” to direct “the hidden life of desire shared between two people.”

When 36-year-old Margaret tells her mother about the 22-year-old boy in her life, her mother calls her “a shocking piece of work,” “a wild woman.” But it is in the wild, the netherworld between a marriage-track relationship and a short-lived tryst, where a couple that isn’t planning for a future but refusing to foreclose one has “brought into existence a new relationship, which is also a way of being.” Like Sylvia and Naomi, Margaret is both survivor and martyr, a stepping stone for Ivan. Still, if she is left indented, she’s also left intact: “He’ll meet someone else, a girl his own age,” she knows, and “her life, after the interlude of their nearness, will resume as before, no worse, and perhaps even for his affection a little better.”

¤

What if, rather than a contemporary bard of straight romance for self-hating white women, Sally Rooney is actually the Gone Girl of heterosexual monogamy? Perhaps she’s been pranking us, or playing a game with sky-high stakes, setting a trap and stumbling back to the suburbs drenched in blood, prepared to take the blame. Maybe it’s all about the way you look at it, the words you choose to describe the scene, whom you’re rooting for and who made the first move. In Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl (2012), Amy Dunne wields misogyny as a blade used as often for self-harm as for full frontal assault. She capitalizes on her husband’s bumbling incompetence and infidelity—along with the fact that most missing women have been murdered by their husbands—to make it look like he committed a crime only she can absolve him of, eventually saving him from literal prison while entrapping him in the figurative prison of their miserable marriage. Reading Intermezzo, I wondered if Rooney was playing a parallel game: revealing the constrictive, claustrophobic nature of heterosexual monogamy while recognizing that such enclosure can comfort as much as it constricts; writing characters who possess the keys to their gilded cages yet choose, again and again, to leave them on the nightstand.

The first time I finished Beautiful World, Where Are You, I rolled my eyes at the ending and immediately told anyone who would listen that it was breeder propaganda featuring fake bisexuals for clout. When I reread it this summer as part of my self-imposed Sally syllabus, I realized that my initial take was exactly what one of the Conversations with Friends girls would have come up with, were she to read and want to skewer the book. Obviously, when I took this show on the road at various bars over the course of August, much of Brooklyn thought I’d lost my mind. People thought Rooney was simply writing about love in the time of capitalism, cosplaying Austen under neoliberalism, or penning CW television plots for adults who want to feel like intellectuals while reading erotica.

This September, Rooney told The Guardian that, had she not “fall[en] in love when [she] was very young” with someone she ended up married to, it would not have been “possible for [her] to write everything that [she’s] written.” The sentiment seems to directly credit her man for her literary output. On the other hand, in her Dublin Review piece, she discussed the art of “deflecting” credit, noting that “in a world saturated with the sounds of male authority, there’s always something ‘not quite’ about a woman’s voice in public” and “there was always a man, somewhere, who could be credited with [her] achievements.” Perhaps it’s about plausible deniability, about ensuring there is always a room of her own in the house of heterosexuality—and a trapdoor.

Maybe I’m misreading everything, but maybe Rooney wants us to. Near the end of her essay “Misreading Ulysses,” Rooney muses that after all her theorizing and analyzing, she does “feel like a little girl who has been allowed to play for too long with her brothers’ toys, and is now surreptitiously making the action figures kiss.” She doesn’t apologize for this, instead arguing that Ulysses is a novel “worth misreading, arguing with, reinterpreting, even rewriting, making our own.” Intermezzo’s epigraph comes from Wittgenstein: “But aren’t you now playing chess?” Language, in the Austrian philosopher’s conception, is a toy set of its own, a toolbox, a series of instruments best played with curiosity, a sense of humor, and a refusal to fear hitting the wrong note. Carrying a tune can be overrated; losing a game might just incite desire. Reposition the pieces on the board, deal yourself back in, play pretend with someone else’s toys—you might realize that breaking the rules was the name of the game all along.

¤

In an auditorium in Belgrade, Serbia, a precocious brunette is having a crisis of conscience. She can win the argument, sure, but at what cost? She sips from a water bottle, victorious, and then comes the white wine, the admiring gazes, the cavernous void and crisp hotel sheets. So she miscast the stakes of the conflict, and the course of it, to convince the judges; so she fooled a man into thinking he made the defining move—put the emotion in her voice to tug on his heartstrings and kept the steel in her eyes, which she knew he wouldn’t meet anyway.

Before the novels or star-studded adaptations, before she was championed the first great millennial author and advance copies of her books became summertime status symbols, Rooney’s essay for The Dublin Review detailed her fraught relationship with her past as a champion college debater. This was the coliseum in which she learned to win, competitively and interpersonally, as well as where she learned to reconsider conversation as a game and conflict as entirely controllable, not to mention contrived. It is also where she learned to wield emotion like a knife, playing into male judges’ misogynistic stereotypes about women’s styles of argumentation to ardently argue points she didn’t believe in at all and take home the prize: the eyes on her at the afterparty, the popularity and the points.

Rooney wanted to win, but she didn’t want to want to win, or to be seen as desiring success. Abandoning the pursuit entirely would mean resigning herself to real life, where arguments have stakes and judges are hard to find, let alone trust; playing to win would mean chugging the cocktail of her own ambition. “Participation in a game, any kind of game, gives you new ways of perceiving others. Victory only gives you new ways of perceiving yourself,” she wrote. “Maybe I stopped debating to see if I could still think of things to say when there weren’t any prizes.” Maybe she’s entered a new ring, and maybe she’s arguing both sides.

LARB Contributor

Emmeline Clein is the author of Dead Weight: Essays on Hunger and Harm (Knopf, 2024) and Toxic (Choo Choo Press, 2023). She covers books at Cultured, and her writing has been published in The Nation, The Washington Post, The Paris Review, The Yale Review, and elsewhere.

Share

LARB Staff Recommendations

-

Emmeline Clein recounts an “American Icarus story” spelled out in diet pills and rhinestones in an essay from the LARB Quarterly issue no. 42, “Gossip.”

-

Emmeline Clein reviews the reissued edition of “Notice” by Heather Lewis.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

Source link