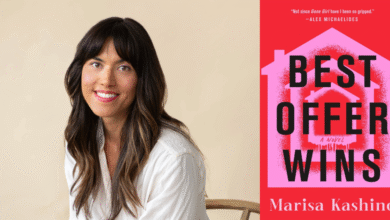

Q&A with Eric Puchner, Author of ‘Dream State’

At the start of Eric Puchner’s new novel, Dream State, we meet Cece, who’s flown to Montana one month prior to her wedding, to take care of last-minute tasks. (First on the list: hiring a square dance caller for the reception.) She’s reveling in the chance to spend weeks at her fiancé’s family’s lakeside cabin, where the wedding will be held.

Early one morning, she dives into the nearby lake and then pops up, hooting from the chill. “In Montana, you hooted in the morning and whooped after lunch,” she thinks to herself. When her fiancé’s best friend, a guy she’s never met, drops by and finds a shivering Cece toweling off, he suggests that, in the future, she wait to swim until after noon, when the water is warmer. Cece’s reply is quick and conclusive: “A person afraid of cold water is a bystander of life.”

When it comes to his characters’ lives, Puchner is no bystander either. Rather than distantly record their comings and goings, he delves into their waking thoughts, their secret ambitions and desires and disappointments, as well as their nighttime dreams. Puchner remains committed to them for 50 years after that 2004 wedding, showing readers the evolution of their marriages, their health, their jobs, their friendships, and their families. But he also imagines a future environment in which global climate change is having real, devastating effects. Cece describes one summer of severe and sudden storms when “rain would machine-gun the windows, flooding the house.”

Dream State has an ambitious, intriguing overall trajectory. There’s a sureness to Puchner’s writing—a sense that, as a reader, you’re in very good hands. I agree with the Kirkus reviewer who called Dream State “sprawling and elegant—a novel that feels both old-fashioned and bracingly inventive.”

Eric has early roots in Baltimore, having attended Calvert School before his family moved to California. He’s now landed back in Baltimore, where he’s an associate professor in Johns Hopkins University’s Writing Seminars. In addition to an earlier novel, Model Home, Eric has published two story collections, Last Day on Earth and Music Through the Floor, which was a finalist for the New York Public Library’s Young Lions Award.

BFB: We both attended Calvert School, where we were taught to outline before drafting papers. Does this early instruction still affect your writing process? Did you chart this novel in advance?

I have no idea how Calvert affected me long term; I do know I have a strong handshake! (We used to shake hands with the principal every morning.) Nabokov, who meticulously outlined his novels on notecards, would no doubt have called me an “amateur,” but I don’t chart my stories or novels in advance. That’s partly what’s fun about it: that it’s exploratory. With Dream State, I had no idea who the characters were, or what the overall plot would be, when I wrote the first draft. E.L. Doctorow said that writing a novel is like “driving at night in the fog: you can only see as far as your headlights,” and my process feels similar.

I did know that I wanted to write about a particular place, Northwest Montana, and a particular house, one based on my father-in-law’s place on Flathead Lake. And I knew that I wanted the antagonist to be time and that the book would cover a great many years, because I wanted to examine the choices people make, both personally (when it comes to one’s life) and collectively (when it comes to the earth), and how these choices have consequences across generations.

I also knew what the fulcrum of the book would be, that it would pivot on a disastrous wedding, one inspired by a wedding I officiated in which half the guests had norovirus: the groom had to sit down halfway through his vows, and one of the flower girls threw up on her way down the aisle. So I knew the book’s first section would move irrevocably toward this sick wedding, though I had no idea the wedding would return again—in a surprising and resonant way, I hope—at the end. (The real-life bride and groom, I should add, have been happily married for 15 years!)

BFB: Dream State delves convincingly into cardiac surgery, equine therapy, wolverine tracking, backcountry skiing, and other endeavors. How much research did you do?

I have a dirty secret, which is that unlike many writers (my wife included), I don’t like research much. That said, I do a lot, because unless you’re writing autofiction and ruthlessly limiting yourself to your own experience, you need to make your vision as credible as possible. I don’t mind reading books, but I prefer to gather information by talking to “experts.”

A good friend is a cardiac anesthesiologist at Hopkins; I’ve long been fascinated by his work, so it made sense to give Charlie, a main character, his profession—partly so I could steal my friend’s stories! After finishing the book, I took him to an epic dinner at Dylan’s Oyster Cellar and read him passages aloud to make sure they were reasonable. Similarly, most of the rehab stuff comes from talking to someone who once struggled with addiction. I learned about wolverining from a wildlife biologist I met in Montana, Doug Chadwick, and his wonderful memoir The Wolverine Way.

I’m an avid, lifelong skier, so that stuff was easy—a great pleasure to write, in fact, as it’s something I love but had never written about before.

BFB: In what ways did other people—either through manuscript feedback or through published works that inspired you—influence the writing of Dream State?

Writing a novel—in my experience, at least—is both solitary and hugely collaborative, depending on what stage of the process you’re in. I wrote the first draft over several years, without showing it to anyone. Of course, there are books that informed the novel in ways I can’t begin to trace. I love novels centered around beloved houses, especially ones that use them as a metaphor for our own impermanence: To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf, The Summer Book by Tove Jansson, Housekeeping by Marilynne Robinson, and Light Years by James Salter, to name a few.

Once I’m ready to show something to people, I don’t skimp! (Though it’s a huge ask, especially with a 500-page manuscript, so I don’t do it lightly.) My wife, Katharine Noel, a novelist herself and an excellent editor, is always my first reader. She read the book countless times. Other readers I know from grad school or Stanford’s Stegner program also gave me amazing feedback. Two of my brilliant colleagues at Hopkins, Andrew Motion and Danielle Evans, were generous enough to read the book as well.

BFB: Occasionally, the narrative slips into the point of view of a non-human character. Did you intend these short POV shifts to complement the book’s overall concern with climate change?

Absolutely. I also thought it would be fun. Many novels I admire have a nimble omniscient narrator who makes surprising leaps in perspective. In Dream State, it made perfect sense to me that we’d occasionally see the world—and the people who are destroying it—from our fellow “earthlings’” perspectives.

BFB: Scenes and details don’t always appear when readers might expect them to—or are omitted entirely. Was it challenging, trusting readers to hold on?

I’m drawn to novels that elide things, that create meaning through what’s left out. On one level, it’s impossible to say what a novel is actually about—really, it’s about the experience of reading it—and absences add greatly to a novel’s emotional effect and meaning. Since so much of Dream State is about ghosts—the “ghost lives” we might have led, the ghosts of loved ones we’ve lost, ultimately the ghost of the planet itself—it made sense to haunt the novel with the sorts of absences you’re talking about, to create a more inventive, dreamlike structure for the book’s latter half. So no, it wasn’t challenging. I prefer novels that put a lot of trust in the reader; the alternative, not trusting your reader enough, is far worse!

—————————————

Come to Bird in Hand at 6 p.m. on February 22, 2025, to hear Eric in conversation with Danielle Evans, author of The Office of Historical Corrections and other works.

Related

Source link