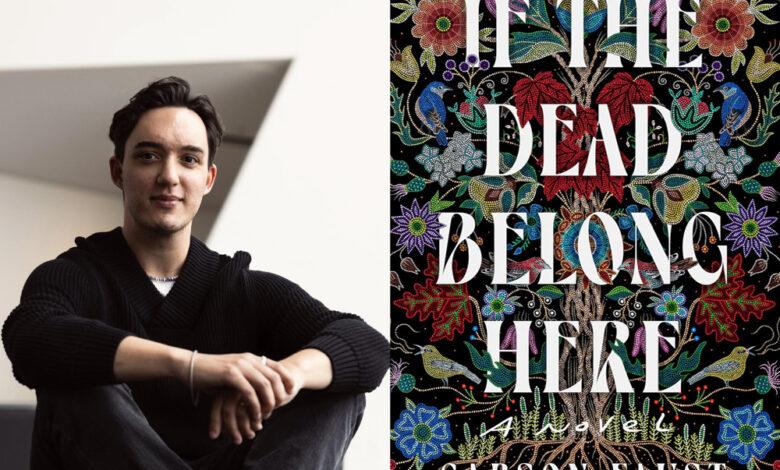

Q&A: Carson Faust, Author of ‘If The Dead Belong Here’

We chat with author Carson Faust about If The Dead Belong Here, which follows a young girl who goes missing and the ghosts of the past collide with her family’s secrets in a mesmerising Native American Southern Gothic.

Hi, Carson! Can you tell our readers a bit about yourself?

While I was born and raised in a small town in Wisconsin, I am an enrolled member of the Edisto Natchez-Kusso Tribe of South Carolina. I’m a Cancer sun with a Sagittarius moon and rising—which mostly just means that, while melancholy is my baseline, I have no choice but to believe that a better and more just world is possible. Here’s an incomplete list of things I love: mall goth sensibilities, reading aloud while alone, midwest emo music, late night walks to a gas station, and crying in the car.

I currently live in Minnesota with my husband, Samuel, and our elder chihuahua, Jacks.

When did you first discover your love for writing and stories?

My love for stories began when I was small enough to sit in the laps of strong women, listening. My grandmas and my great-aunt would read fairytales and ghost stories to me. That’s where my love of storytelling began. They would read stories about witches or, sometimes, tell me about ghosts they’d spoken with. I saw how they read and shared stories and knew I wanted to try my hand at it as soon as I could.

Quick lightning round! Tell us:

- The first book you ever remember reading: Bruce Coville’s Book of Magic: Tales to Cast a Spell on You.

- The one that made you want to become an author: Paradise by Toni Morrison.

- The one that you can’t stop thinking about: as if fire could hide us by Melanie Rae Thon

Your debut novel, If the Dead Belong Here, is out now! If you could only describe it in five words, what would they be?

Mike Flanagan goes Indigenous gothic.

What can readers expect?

If the Dead Belong Here begins with the disappearance of a six-year-old girl named Laurel. After Laurel’s disappearance, her family begins to unravel, reopening old wounds that spur her older sister, Nadine, to grapple with their past. Nadine must turn to her elders, and even to the dead, in an attempt to bring her sister home.

Yes, this is a novel about loss, but it’s also about ghosts that follow you. Haunting is a form of connection, so this story is about the gifts that the dead can give us—however terrifying they may seem. How can our dead keep us connected to our traditions, to our language? And what might these connections cost us?

Where did the inspiration for If the Dead Belong Here come from?

This novel is one about inheritance. I believe all people carry an inherited history. Sometimes this can feel farther away from us. Sometimes its just one generation removed. If the Dead Belong Here is my attempt to show how these inheritances can intersect. For example, as I was growing up, my father seldom discussed the death of his brother, Shane. Shane was hardly fifteen when he was killed in a car accident. The silences I grew up with—especially those surrounding my uncle’s death—shape this book. Writing it became a way to ask questions I hadn’t always had the language to for. This novel is my attempt to weave family histories to our people’s traditional stories and folklore. Many of the stories I turned to came from my grandma. Listening to her stories helped me feel greater connection to our lineage.

For example, learning about the ucv’ske—the Little People in Natchez stories who appear in this novel—reinforced the familial themes I saw emerging. The ucv’ske are tied to silence. You mustn’t speak of them at the wrong time as there can be harsh, or even deadly, consequences. They only appear if they choose to. They can make you disappear. Some say they guide our dead to the afterlife. They more I learned, the more I saw those themes—disappearance, death, silence—mirrored in the characters here.

Interrogating my family’s past had its own rules as well: Ask the right person at the right time. Knowledge has consequences. So does forgetting. That tension is everywhere in this book.

Were there any moments or characters you really enjoyed writing or exploring?

I think the intergenerational relationships within this novel are the ones that interested me the most. My elders had a large hand in raising me, so I aimed to capture how nuanced and special connections between young folks and older generations can be. In the novel, Nadine is required to be very precocious due to the fact that her mother is unable to be there for her—largely because her mother has significant depression and a substance abuse disorder. It would be easy to imagine Nadine as a kid who thinks, Why would I need my auntie’s help? What could she know that I haven’t figured out for myself? I’ve made it this far. And there are times where that’s her impulse. But Nadine also finds ways of being receptive to help and guidance. She is able to shirk that toxic individualism that can weigh people down.

Did you face any challenges whilst writing? How did you overcome them?

For me, writing is less an exercise in creating something. I consider writing to be an exercise in listening. Characters visit me, and it is my job to get their stories down as best I can. The challenge here, and the challenge while writing, is the same one you’re presented with when meeting anyone new. You have to ask them the right questions. You have to figure out what makes them tick. You have to figure out what they want from you and what you want from them.

There were characters who were easier for me to inhabit. For example: The melancholy that Ayita experiences was easy for me to bring to life on the page given that that feeling is my home base. While inhabiting Nadine’s righteous anger was more challenging at times. I made sure to consider what kinds of events would most trigger Nadine. At just fourteen, she’s endured a lot. It takes a lot to get under her skin, so I took my time to ensure any reactions felt true to her.

This exercise in listening isn’t just about hearing your own characters out. Anytime I hit a difficult spot, I turn to the works of other writers. My mentor, Diana Joseph, has a practice that’s never failed me: If you’re stuck inside your own writing, find a book you love and write it out slowly, word-by-word.

This is your debut novel! What was the road to becoming a published author?

I’ve been thinking about the distinction between being a writer and being an author a lot in the lead-up to publication. Writing is a practice and a discipline that brings me hope. And, sometimes, the process of seeking publication can bring feelings of hopelessness, doubt, and frustration. I was chatting with a writer friend of mine, Alejandro Heredia, who distilled it pretty perfectly: “You have to want to be a writer more than you want to be an author.” I think that holds true, but I also recognize that I’ve been very lucky to have found a team that understands the stories I want to see in and shepherd into the world.

I met my agent, Annie Hwang, at an online conference during the COVID-19 lockdown days. She worked with me for several years refining and reimagining my manuscript, readying it for submission to publishers. During submission, when I had the privilege of meeting my editor-to-be, Ibrahim Ahmad, I knew he saw the characters in this novel fully. He saw them as I did. He recognized the hope they carried that so many other editors failed to notice. A lot of others only saw the heartbreak. The process of bringing this book to life has reaffirmed for me the importance of finding folks who court possibility.

What’s next for you?

I’ve been drafting a second novel for several years now. It feels good to be able to spend more time with new characters even though I still have a lot of love for the folks in my debut. What I’m most excited about is the breathing room this new novel allows. To my mind, most debut novels serve as an origin story in some way. That’s how mine felt to me, too. I felt a lot of responsibility to get the history of my tribe and my people correct. I read through census records and affidavits and anthropological research—largely because I knew my debut was about looking backward and honoring our stories.

This second novel feels a lot more forward-facing. It also feels more fully grounded in South Carolina, whereas my debut kind of walked in two worlds. This new work still has all the horror elements—and plenty of ghosts. In some ways, it feels like it might be a more traditional ghost story. Whatever the case may be, I’m excited to see where these new characters take me.

Lastly, what books have you enjoyed reading this year? Are there any you’re looking forward to picking up?

I mentioned Alejandro Heredia above. His debut novel, Loca, was the first book I read this year. It’s a novel that pays close attention to the ways friendships shape our lives, which I appreciated. A fun coincidence is that two writers who attended I attended Tin House Summer Workshop with in 2020 had their debuts come out this year as well. Eliana Ramage’s To the Moon and Back and Jon Hickey’s Big Chief are books I’ve been looking forward to since reading partial drafts in that workshop setting. Right now, I’m reading a forthcoming project from Mathilda Zeller, whose story “Kushtuka” appeared in Never Whistle At Night. It’s exciting to see Native writers working across genre: science fiction, political, and horror, in these cases. Next year, I look forward to Jenzo DuQue’s debut collection, The Rest of Us. I’ve followed Jenzo’s work for a long time now and I can’t wait to have his book in my hands.

Will you be picking up If the Dead Belong Here? Tell us in the comments below!

Source link