America’s Greatest Mistake – The American Prospect

This article appears in the October 2025 issue of The American Prospect magazine. Subscribe here.

The World’s Worst Bet: How the Globalization Gamble Went Wrong (And What Would Make It Right)

By David J. Lynch

PublicAffairs

For a time, globalization was synonymous with utopia: the untrammeled flow of capital across borders, new markets waiting to be opened, the growth of developing nations flaunting their comparative advantage in manufacturing jobs. If you covered the chaotic end of Suharto’s rule in Indonesia, the ruble crisis in Russia, China’s integration into global markets, and the plight of abandoned American workers, however, you may be convinced globalization is the single-best explanation for the economic upheaval and political polarization of our current age.

This is where David J. Lynch, a longtime global economics reporter for The Washington Post, has landed. For years, he has covered every major trade agreement and its impact on workers around the world. In The World’s Worst Bet: How the Globalization Gamble Went Wrong (And What Would Make It Right), he delivers a new history of the euphoric rise and eventual backlash of this era of the connected world.

Living through the past decades, you may feel like you know the story all too well. But by focusing on the tension between capital and labor, he brings fresh insight to the weighty decisions and missteps that brought us from the heady days of neoliberalism to the full-on return of a nationalist world order.

Lynch structures the book as a narrative autopsy of each presidential administration’s respective failures to shield the American worker from globalization’s most backbreaking consequences. Anchored in exhaustive reporting and dozens of interviews with those who built or challenged the system, it is a Greek tragedy of messianic, world-shaking hubris, starring an elite class of politicians whose betrayal of working-class Americans helped trigger a populist surge that has engulfed the world.

IN THE 1990s, PRESIDENT BILL CLINTON viewed globalization as an unparalleled force for spurring prosperity at home and spreading political liberalization abroad. He lifted barriers to trade, signing the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and bringing China into the World Trade Organization (WTO), which was founded in 1995 to establish the rules of global commerce.

While most Americans supported China’s accession to the WTO, nearly three-fifths believed that workers at home would suffer. In the academy, economist Dani Rodrik argued that gains for investors and high-skilled labor would come at the expense of low-skilled and less-educated workers, whose jobs would be taken by Chinese labor. Over time, Rodrik added, this gap would foment social and political tensions, while increased mobility of capital would make it easier for corporations and the rich to dodge taxation.

Clinton wasn’t ignorant of such concerns, Lynch notes. Yet he saw himself as a realist. Companies had been shifting blue-collar jobs overseas anyway; better that the U.S. get some benefits in the exchange. To offset the pain for workers, he turned to his party’s favored solution since the Kennedy years: “trade adjustment assistance” (TAA), or investments in job training, infrastructure, and technology to ease workers into more productive industries.

TAA had long underperformed, thanks in part to cumbersome application processes that sharply limited enrollment, Lynch writes. Only 10 percent of eligible workers received benefits. Yet Clinton still saw TAA as the cure for what he was about to unleash on workers, including a version of it in NAFTA. Whether due to deficit hawks in Clinton’s own party or House Republicans who took over after the 1994 midterm elections, TAA once again failed to deliver much more than meager charity for workers undercut by offshoring.

After NAFTA’s signing, factory employment remained stable. But workers most exposed to competition from Mexico were hit hard, spurring working people to believe the Democratic Party had abandoned them and fueling a wave of anti-globalization protests that crested at the WTO’s meeting in Seattle in 1999. Led by trade expert Lori Wallach, activists succeeded in blocking new trade talks, but only after a violent crackdown by authorities.

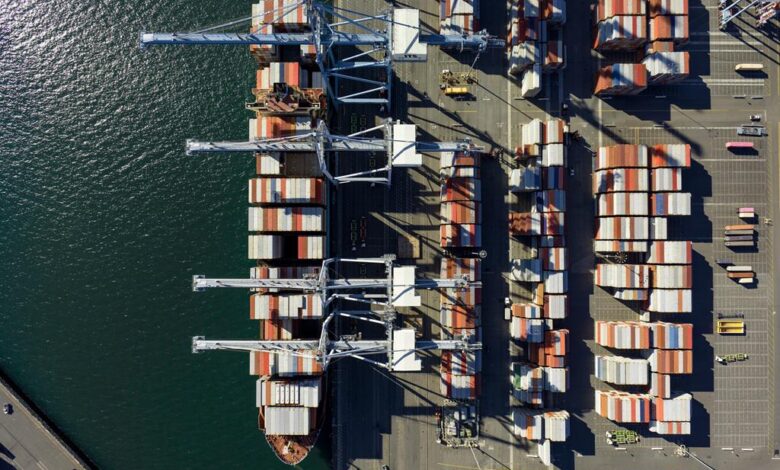

China started slashing tariffs and courting investors in the early 1990s. After joining the WTO, it revised thousands of regulations in accordance with the body’s rules. In the first six years of its membership, U.S. investment in China more than doubled, and firms devised globe-spanning, super-lean supply chains, slashing inventories by almost a third between 1992 and 2005. “Just-in-time” logistics exacerbated the risks of supply chain disruption, but executives saw them as a boon for their stock prices, Lynch writes. And with China committing to market liberalization, political reform would soon follow. Or so the end-of-history thinking went.

Then unexpected things began to happen. Imports from China spiked by 50 percent in the first three years of its membership in the WTO; wasn’t it supposed to go the other way around? Beijing also began flouting its trade commitments, particularly around subsidy phaseouts.

Perhaps the most alarming development was the hollowing out of blue-collar America. In 2016, economists David Autor, David Dorn, and Gordon Hanson published a paper on the “China shock,” estimating that low-wage Chinese competition had taken some 2.4 million American jobs from 1999 to 2011. While companies benefited from cheaper Chinese products, slightly increasing U.S. employment, the job losses that did occur were concentrated among less-educated and less-skilled Americans, just as Rodrik predicted.

WITH A FEW INEFFECTUAL EXCEPTIONS, the Republican Party under George W. Bush showed little interest in either trade enforcement against China or trade adjustment assistance for impacted workers. By the mid-2000s, Washington was spending a smaller share on education and training than it did at the end of the Cold War. Even the halting efforts toward protectionism were ill-fitting. Bush, heeding the lessons of the Democrats’ fallout with West Virginia steelworkers, tried to use tariffs to protect their industry, only to have the WTO rule them illegal.

The massive trade surplus with America meant China was flush with dollars that it plowed into low-risk U.S. Treasurys. Eventually, Beijing became the single-biggest holder of U.S. government debt, giving it immense power over Washington. For Americans, it also helped keep borrowing costs low. This would prove toxic. Bush argued that construction jobs created by the ill-fated housing boom could help fill the gap left by the vanishing manufacturing sector. When the bubble popped, so did the remnants of that strategy.

As a senator, Barack Obama observed that globalization had “changed the rules of the game,” leading to the loss of jobs, health care, and retirement security. As president, Obama’s Affordable Care Act and stimulus would attempt to stanch some of the bleeding. But few of his insights about globalization carried over to his presidency, even as Beijing’s litany of misbehaviors expanded.

Undervaluing the yuan made China’s exports ultra-cheap. Its state-backed corporate espionage operation was responsible for an estimated 50 to 80 percent of global intellectual property theft. Stories emerged of Chinese regulators coercing U.S. companies into reincorporating in their country or even selling to state-backed private equity funds for a fraction of their value.

Yet Obama would continue to regard globalization as the righteous path, while continuing to inadequately compensate the policy’s losers. In 2011, Goodyear closed a plant in Union City, Tennessee, laying off 1,900 employees. Of those who finished TAA-funded training, only a little over one-third found work in their new fields, Lynch writes. Those who did saw their earnings shrink, in some cases by half.

To sway China’s neighbors into the U.S. sphere of influence, Obama pushed for the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a 12-nation free-trade pact with Asian and South American countries. Wallach, Republican attorney Robert Lighthizer, and a cadre of anti-globalization activists viewed the TPP’s pro-business protections, including a provision allowing companies to sue governments for passing laws that weaken future profits, as evidence that corporations would continue to take precedence over labor and the environment. White House polling showed that while college-educated Democrats and left-leaning independents generally supported the TPP, Republicans no longer supported trade deals, with particularly fierce opposition from non-college-educated whites.

Obama ultimately secured a “fast-track” process allowing a yes-or-no vote on the TPP’s passage, but only after 151 House Democrats voted against his initial attempt. In the end, both candidates in the 2016 presidential election turned against the TPP, and the winner rejected it on his first day in office.

IN DONALD TRUMP’S OPINION, free trade had allowed a cabal of global elites to destroy American workers, either replacing them with faceless hordes of immigrants or shipping their jobs overseas. On the campaign trail, he warned that Hillary Clinton, who had backed the TPP before later rejecting it, would extend her husband’s trade legacy—a potent, effective attack.

After plowing through the GOP primary field and defeating Clinton, Trump declared war on trade, setting about renegotiating NAFTA, engaging China in contentious trade talks, and tasking Lighthizer, his top trade official, to use targeted tariffs in a blunt attempt to force reshoring.

Yet his nationalist agenda, assembled without any input from labor groups, fell short, Lynch writes. The United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement, NAFTA’s successor, largely resembled its predecessor. With China, Trump suspended a threatened second round of tariffs in exchange for a promise from President Xi to buy more U.S. goods. Structural concerns that Lighthizer had raised around things like intellectual property went unaddressed.

COVID-19 initially ground the world economy to a halt, but quarantining consumers, boosted by federal aid, started shelling out for furniture and fitness gear. Panic buying exacerbated shortages of everything from medical equipment to computer chips. The world had absorbed the risks from hyper-lean global supply chains before, notably after the 2011 tsunami that hit Fukushima, Japan. But businesses were completely unprepared for rapid consumer shifts and haphazard lockdowns at Chinese factories.

As a result, inflation jumped to levels not seen in nearly half a century. By the end of January 2021, ocean-shipping costs had skyrocketed by 80 percent. Executives around the world were forced to accept that just-in-time may have gone just a bit too far.

Joe Biden had backed NAFTA and Beijing’s integration into the global economy as a senator. But the China shock changed his mind, convincing him to vote against trade agreements and support punishing China for devaluing its currency. As vice president in the age of Occupy and the Tea Party, he questioned whether free trade could deliver for working Americans.

As president, Biden pledged to break with globalization and re-center U.S. workers, with hundreds of billions in fresh spending for American-made computer chips and clean energy, leading to record-high spending on factory construction. Defying environmentalists, he slapped a 100 percent tariff on China’s electric-vehicle sector and other clean-energy components, while keeping in place the bulk of Trump’s tariffs. Yet there was little hope of reversing a 70-year slide in manufacturing employment, one fueled largely by automation, and, later, by NAFTA and the China shock.

In the 2024 election, the Democrats would be doomed in part by Biden’s pursuit of a second term despite his evident infirmity. But Vice President Kamala Harris’s failure to articulate a working-class economic agenda and speak to voter concerns about runaway inflation once she replaced him on the ticket showed, yet again, how little the party had learned.

Since reclaiming the presidency, Trump has decimated large parts of the federal bureaucracy, delivered a massive tax cut for the rich, launched a deportation army, and unleashed a flurry of new trade wars. Without Lighthizer’s steadying hand, the tariff regime has been chaotic, and unpopular amid inflation fears. It has not delivered promised benefits for workers; manufacturing employment has fallen for six straight months as of August, and the spike in factory construction is over.

Even amid the tariff wars, nearly $600 billion worth of merchandise passes between the two nations each year. And China remains an irreplaceable supplier for American manufacturing. Those salivating for a true break may be disappointed, Lynch suggests.

NEAR THE END OF THE BOOK, Lynch presents a statistic sure to haunt even the most die-hard globalization evangelist: In places hit hardest by China’s rise, Washington has spent more than 30 times as much per person on lifetime disability benefits than on TAA.

For the true believers, Lynch recommends some soul-searching. Writing off defenses of the manufacturing work central to the fabric of countless small towns as “ignorant protectionism” appears to have done little good. “Treating the livelihoods of individuals and communities as just another variable in an equation might be the right way to run a regression, but it was the wrong way to win and hold political power,” he writes.

Yet these individuals and communities are largely absent from his book. So too is any extended discussion of trade’s disparate impact on different ethnic groups, much less between genders. Lynch’s policy prescriptions also feel unsatisfying: He recommends rebuilding our tattered social safety net via higher corporate tax rates and a renewed commitment to ending tax avoidance. For Lynch, proposing policies seems less important than forcing a reckoning with a world of borderless capital, an all-powerful China, and populist tumult.

Inevitably, Lynch’s book leads him back to Bill Clinton, the man who started it all. While he accepts that globalization hasn’t worked out the way he’d hoped, he regards the backlash as a combination of economic, social, and cultural factors. In his mind, there’s still time to find a new script for globalization, and this time, to do right by the American worker. “The obligation of the government is to minimize loss and find people something else to do so we can keep growing.”

Source link