Alexis Wright has revitalised Australian literature, but a new book by a ‘superfan’ overlooks an important aspect of her work

Is there an author more fêted and adored in Australia right now than Alexis Wright? In the two years since the publication of her fourth novel, Praiseworthy (2023), she has been garlanded with awards and ascended to new heights of international recognition, including entering the betting table last year as a possible candidate for the Nobel Prize for Literature. Ladbrokes put her odds of winning at 8/1, before suspending any further bets on her.

It seems only fitting that Black Inc. has decided to place the spotlight on Wright for the final volume of their provocative “Writers on Writers” series. Endlessly experimental and uncompromising in her vision, Wright has pioneered new vocabularies and narrative techniques in her quest to mould the English-language novel into a form capable of expressing a sovereign Aboriginal worldview.

Review: On Alexis Wright: Writers on Writers – Geordie Williamson (Black Inc.)

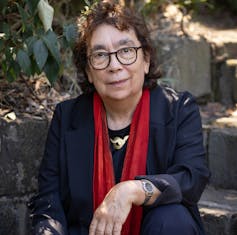

Black Inc. has defied expectations by not commissioning a First Nations author to reflect on the significance of Wright’s work. Instead, the honour has gone to Geordie Williamson, a white settler author, who takes care to note that not only is he a “superfan” of Wright’s work but a personal friend.

Black Inc.

Williamson is an interesting choice, as he is predominantly an essayist and reviewer rather than a creative writer. He writes with an awareness of his non-Indigenous background; indeed, he takes the opportunity to explore how Wright’s work forces him to confront his own settler-colonial guilt.

A discomforting binarism creeps into Williamson’s analysis, which, in its attempt to foreground the ineluctable framework of settler Australia, somewhat inadvertently ends up reinforcing its immanence. “Literature in Australia has two beginnings,” he argues: Indigenous and non-Indigenous.

He acknowledges that Indigenous tradition is “immemorial, old as the first songs sung by the first peoples to have arrived more than two thousand human generations ago”, but the literary history he glosses for us is a settler one. He reminds us that the 19th century Supreme Court judge and poet Barron Field once argued that “real” literature could not happen in Australia.

In this manner, Williamson situates Wright’s work within a deeper history of anxiety over Australia’s cultural legitimacy, and the colonial doctrine that the

very climate and physical landscape of the Antipodes somehow rendered literary production impossible.

Williamson chooses to read Wright’s work through the lens of poetry, emphasising the extent to which Wright’s work pushes at genre boundaries and runs roughshod over literary categories. The names he invokes in a brief literary history are mainly poets: Field, Eliza Hamilton Dunlop, Charles Harpur and Judith Wright.

Abigail Varney/Giramondo

Placed against the wispy concision of settler poetry, the weightiness of Wright’s tomes become even more apparent. The expansiveness of her unbridled narratives points to the choral nature of their intertwined stories, which must be sung together to fully capture the depths of this continent.

Poetry or music does often seem like the most appropriate touchstone for Wright’s prose because it breaks, in such a distinctive way, from the staid, familiar cadences of standard English. Her work is frequently described as “epic” and “operatic”. Williamson calls it her “big-sky style” – a term that accurately captures Wright’s talent for bringing the wider cosmos into the lives of her small-town characters.

Rewriting the land

Williamson suggests that the key to Wright’s work lies in her ability to evoke the deeper rhythms of the Australian landscape. As he puts it: “no one’s sentences fret themselves to the contours of the landscape quite like hers do”.

In what we might see as her overarching project of rewriting the land, Wright reconfigures and negates the settler fiction of terra nullius. She is engaged in a type of terraforming. She pushes aside the myth of a desolate landscape, buries it in irrefutable proof of the land’s fecundity.

In Wright’s novels, Country itself becomes a living, breathing source of artistic sustenance. Characters such as Ivy Koopundi in Plains of Promise (1997), Angel Day in Carpentaria (2007) and Oblivia in The Swan Book (2013) are condemned to twilight existences when they are off Country.

As this book traces a path through Wright’s major works – four novels and a collective biography – it becomes clear how closely connected her themes are. Activism and Aboriginal sovereignty dovetail with the imperative to find a new language to express the collective danger of climate change.

Williamson ends with a postscript where he contemplates his own settler-colonial background and the way Wright compels her readers to reassess their own relationship to the land. He talks candidly about white guilt and admits to feeling “condemned” by Wright’s work.

But he also asserts that “what is crucial here is that guilt is a starting point and not an end designed for some self-loathing middle-class audience to marinate in”.

In many respects, this willingness to speak about white settler guilt is a welcome addition to a public discourse that has become increasingly polarised and incapable of talking with any nuance about race. Yet Williamson’s efforts also highlight the solipsism of white guilt. They remind us of the care needed to ensure First Nations people are not reduced to mere objects for self-reflection.

Wright’s work, from the start, has been overwhelmingly read within the limiting, dichotomous framework of Blak and white Australia. This is a binarism that Wright herself has contested time and again. She has looked overseas for inspiration from non-Anglophone literatures and deliberately included a range of multicultural figures in her work. Carpentaria features Afghan cameleers. Aboriginal characters in Wright’s novels, such as Dance Steel in Praiseworthy, often have Asian heritage. Wright herself had a Chinese grandfather.

Williamson’s decision to focus on Australia’s relatively short settler history passes over one of the most important aspects of Wright’s work: the debt she owes to a pantheon of authors from around the globe. He alludes to the fact that she is “widely and deeply read, with literary tastes that are unexpected, subtle and catholic”. However, it might have been worthwhile taking the time to acknowledge some of the literary giants who have helped Wright find her unique voice and method.

Wright has not mounted an assault on the spareness of Australian literary history by herself. She has drawn from writers such as Carlos Fuentes, Pablo Neruda, Günter Grass, James Joyce, Ralph Ellison and Toni Morrison. She stands with the voices of her ancestors behind her, armed with the precedents set by a formidable canon of world literature.

Williamson is correct to suggest that Wright’s fictions offer a starting point for us to begin a complete re-envisioning of Australian history. This might be one where settlers are not always considered white and where First Nations people are not always and only viewed through the artificially imposed category of race. If we are really to follow Wright’s lead, then perhaps it’s time to start acknowledging that Australia is a country with more than two sides.

Source link